After the record losses seen in credit markets this year, whether in high yield, investment grade, or emerging markets, investors are licking their wounds. The question now is whether it’s worth investing in credit and, if so, when would be a good entry point?

Our stance towards credit has not changed since our Outlook 2022 in November. The fact that the US Federal Reserve (Fed) continues its strategy of aggressive rate hiking to counter soaring inflation, and so risking a recession, confirms this view. We remain very cautious and selective, especially towards high yield and emerging market bonds.

Further spread widening, even after some recent consolidation, still looks on the cards. While investment grade credit would likely suffer in such a broader widening trend globally, the room for substantially more spread seems comparatively limited, in our view.

Three reasons why spreads are still exposed to additional widening stand out

- Growth risk and inflation

- Central bank paradigm shift

- Debt levels and credit quality

1. Growth risk and inflation

After a brief and very sharp recovery in most leading economies and emerging markets, growth is expected to consolidate, in some cases substantially. The International Monetary Fund predicts that global growth will slide from 6.1% in 2021 to 3.2% this year, with the risk for growth skewed to the downside. While the US economy has already contracted for two consecutive quarters, output in the eurozone and the UK is at high risk of shrinking in the final quarter of this year.

While there has been no notable correlation between spread and economic growth throughout the recent past, the mix of weakening household consumption, margin squeeze, and revenue risk on the corporate side leads us to suspect that the credit quality of issuers may worsen. Indeed, the European Commission’s businesses and consumer surveys reveal that 45% of companies in the industrial sector were facing shortages limiting their production in July, not a good backdrop.

Additional pressure looms given the potential for energy rationing in continental Europe if gas supplies through the Nordstream 1 pipeline remain restricted. Any rationing would hit energy-intensive sectors like chemicals, concrete, and autos the most. However, consumer cyclical sectors would also be hurt as consumers’ spending power is squeezed.

A stagflationary scenario seems a high possibility in the eurozone. This additional risk is partly reflected in spreads which in respect of high yield (115bp premium) and investment grade bonds (40bp premium) are trading well outside of US spreads, for example. Selective positioning in more defensive sectors and focusing on investment grade seems appropriate as the tail risk remains high.

2. Central bank paradigm shift

The reason for a weaker correlation between economic output growth and spreads has often been due to central bank intervention with the aim of counteracting further spread widening during difficult phases, as seen during the pandemic in 2020. But such a central bank “put” is vanishing, as the Fed, the Bank of England (BoE), and the European Central Bank (ECB) shrink their balance sheets and let some bonds mature.

The ECB stands out with a sizeable balance sheet that equates to 80% of the region’s gross domestic product. The termination of the central bank’s existing APP and PEPP programmes and the prospects of higher rates prompted a significant widening in Italian bond spreads, which at 230 basis points (on the basis of the 10-year yield compared to German 1-year bund yields) are still close to the peak seen in June.

We believe that volatility may intensify in this area and would not be surprised if the market tests the effectiveness of the ECB’s new transmission framework, which allows selective bond buying during distressed times.

This is not to say that central bank-induced volatility will only be contained to the eurozone. The BoE is likely to start selling out its APF (asset purchase facility) portfolio from September. Such selling would hit a relatively small and illiquid bond market, which would likely leave spreads exposed in an already vulnerable market.

3. Debt levels and credit quality

As much as $305 trillion of equivalent debt has been amassed globally, according to the Institute of International Finance (IIF). The latest expansion occurred on the back of the pandemic. A typical and healthy repair phase, characterised by deleveraging, has been missing during this very short credit cycle, or perhaps an intermediate stage of a larger credit cycle. The increase in debt was mainly driven by non-financial corporates (up $14 trillion since 2019) and general government borrowing.

Despite the higher debt load, corporate fundamentals appear reasonably healthy.

The corporate bond market, in general, is still in a rating-uplift cycle, one supported by improving credit metrics. In the US, for example, the average gross leverage declined to below 2.5 times (debt/EBITDA) while interest coverage is at the top of the range seen over the last 30 years. In addition, larger issuers have been accumulating cash during the pandemic which for now is acting as a cushion.

But this situation is likely to take a turn for the worse and fundamentals for high yield issuers in particular are likely to deteriorate. For example, rating agency Moody’s expects that the average interest coverage for B3-rated companies, which are funded mostly with floating rate debt, will fall below one times (that is, insufficient cash to service interest cost) if policy rates were to rise by 300 basis points (bp) in the US this year as seems likely. Another reason to stick to higher-rated credit, in our view.

Furthermore, speculative grade default rates globally are likely to rise towards over 3% by next year, with significant upside risk depending on the inflation and growth path.

Spreads set to widen

Every economic slowdown, or recession, is different and it is hard to quantify the magnitude of any consequential spread widening in each bond segment. While inflation and higher rates pose risk, we are unlikely to see similar spread levels as seen during the pandemic. In Europe, investment grade spreads towards 300bp could be possible should we see tighter gas supply, for example. This might lead to spreads heading towards at least 800bp for high yield bonds.

While spread widening seems possible, a widening of this magnitude suggests a very pessimistic scenario. As seen during the European sovereign debt crisis in 2012, US spreads would also likely be impacted in an adverse scenario.

But what if the worst is still to come?

Where does this leave investors trying to catch the peak of corporate bond yields and fearing that the worst is still to come? Spread widening is one part of the equation, while the path for rates must also be taken into account.

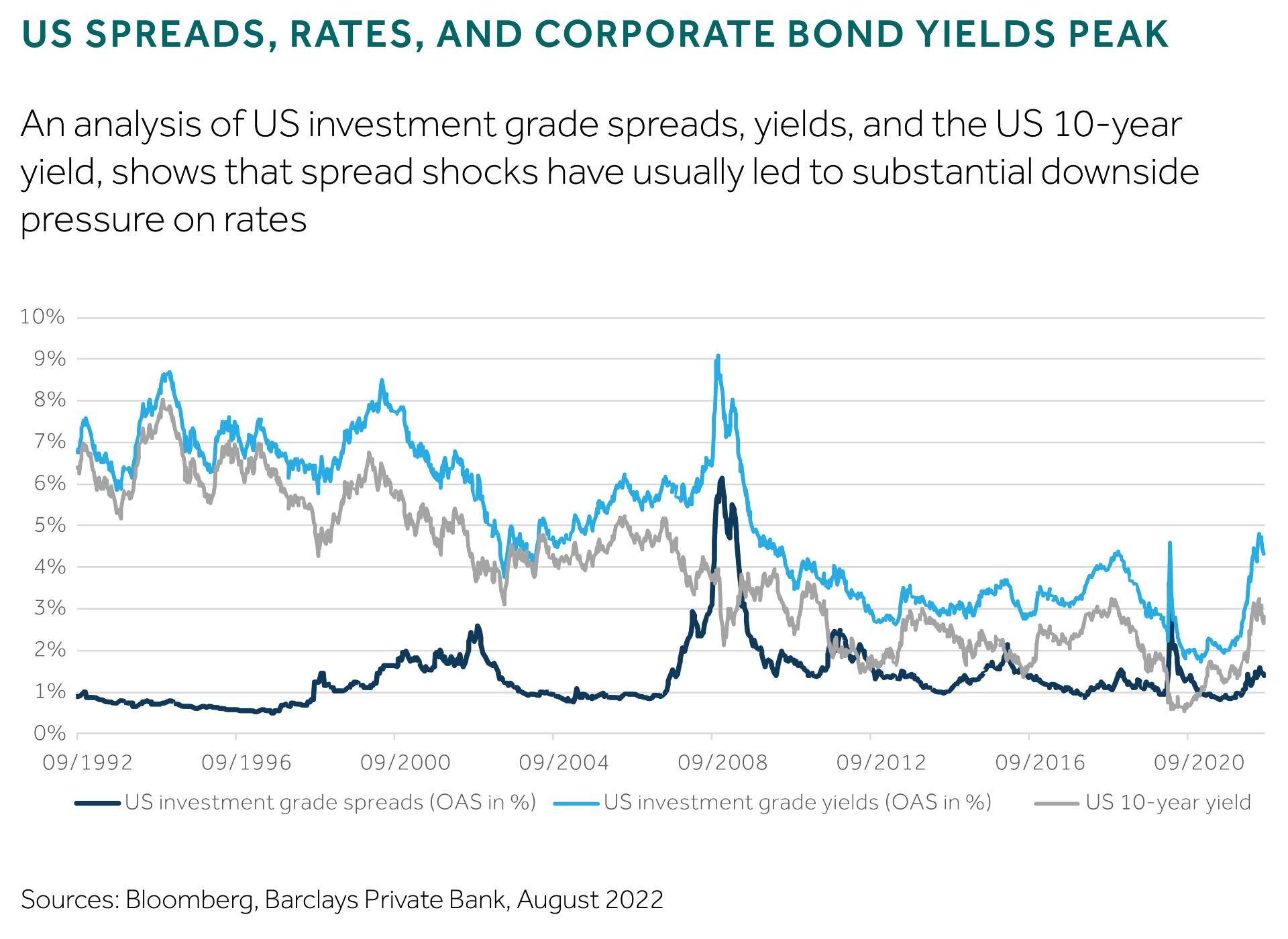

And while this year rates and spreads have moved up simultaneously, thereby exacerbating the losses, they rarely trend in line with each other. While not significant, often there is a negative correlation reflecting the traditional framework that higher rates would usually lead to lower spreads, implying a constructive economic outlook.

The peak yield of corporate investment grade bonds has often coincided with the top in rate levels rather than spread levels. Only in distressed scenarios, or in the case of very depressed rate levels, did the peak in spread levels lead to a peak in corporate bond yield levels, like seen during the credit crisis in 2008, or more recently in 2020’s pandemic.

Interestingly, even after the outsized 120bp move in USD investment grade spreads during the pandemic crisis, corporate bond yields were around 4.6% on average. This compares with the 4.4% peak seen in 2018 and the 4.7% seen in July (see chart).