The question for 2022 is at what speed will yields “normalise” and what does “normal” look like? Another important focal point is how various segments of the bond markets behave as fiscal and monetary support is withdrawn. The answer will dictate prospects for the asset class.

This has been a rollercoaster year for global bond markets, one characterised by a gradually improving global economy, COVID-19 setbacks, inflationary fears, distress within the Chinese property sector and increasingly hawkish signals from central banks.

In this precarious environment, the Bloomberg Global Aggregate Bond index was in negative territory in 2021. It is little comfort for investors that the index has never performed negatively in two subsequent years over the last 20 years, given the unprecedented challenges ahead.

Transitory versus stickier inflation

The narrative of the US Federal Reserve (Fed) throughout 2021 was to look through a limited period of higher transient inflation, and not to respond with premature rate hikes in line with their new framework of average inflation targeting (FAIT). For now it appears that inflation is likely to be stickier than initially anticipated.

Higher inflation already on the cards

Personal consumption expenditures (PCE), the Fed’s main inflation gauge, is less impacted by higher shelter costs (15% versus 40% in the consumer price index). The central bank has already indicated that higher rents and house prices are worth monitoring, as they may reflect the impact of lower unemployment rates. In fact, the Fed has already raised its forecast for PCE, to 2.3% in 2022, while it expects the unemployment rate to decline to 3.8% by the end of next year.

Will the Fed lose its patience?

For now, the bar for the Fed to push hikes forward seems high. First, the Fed’s own inflation forecast points to a moderation of inflation going into 2023 (PCE: 2.2%).

Second, Fed chair Jerome Powell is likely to put much more emphasis on a broad-based, and inclusive, recovery of the US labour market. In doing so, he may be willing to accept a longer period of higher inflation.

Another Fed U-turn possible?

The risk that the Fed needs to adjust tack on rate hiking in 2022, similar to during the hiking cycle of 2018/2019, is significant. Back in 2019, the Fed resisted for a while only to initiate the infamous “Fed U-turn”, dissolving the then inverted curve. Should inflation prove to be more persistent, the rate curve might steepen to reflect the risk that the Fed may fall behind the curve.

What might trigger a change?

The Fed will ultimately be guided by inflation expectations. For now, the 5 year 5 year forward inflation breakeven rate, which measures expected inflation for the five-year period starting in five years’ time, still trades below levels seen prior to 2014, at around 2.5%. Only rates above the 2014 highs might potentially put more pressure on the Fed to act earlier.

The central bank is also likely to observe inflation surveys like the ATSIX (Aruoba term structure of inflation) calculated by the Philadelphia Fed. This measure, at 2.25%, is higher than seen in 2020, but doesn’t point to excessive long-term inflation.

Two steps forward one step back

Since the September Federal Open Market Committee meeting, it appears that more Fed members favour a first rate hike in 2022. While these are mostly non-voters, persisting inflation would strengthen the case for a hike next year. The rate market is already pricing in two hikes for 2022. While this is not impossible, we see a higher probability of one hike later in 2022.

Inflation and slope in focus

On the long end, we believe rates may spike above 2% but this should be only temporary. Our view stems from two main factors: first the inflation path, and second the yield curve pattern. As mentioned previously, we believe inflation won’t run away. On the curve side, it’s important to assess what the fair level of the long-term fed policy rate might be.

During recent decades, the Fed’s neutral rate has regularly been revised down. In 2012, the neutral rate in real yields was 2%. Only a substantial change of estimates over long-term trend growth, increase in labour force growth, and change in structural inflation dynamics would lead to a higher neutral rate, as per the Laubach-Williams model. Without this, the Fed may find the urgency to counteract the large debt overhang and lower trend growth with the help of a lower equilibrium rate.

We see a high probability of rate volatility, with the curve steepening in the next few months before potentially flattening as the market starts pricing in more hikes later in 2022

Given this overarching uncertainty, we see a high probability of rate volatility, with the curve steepening in the next few months before potentially flattening as the market starts pricing in more hikes later in 2022.

Risks abound

Outside of our base case, the risk of persistent and elevated inflation and higher rates should not be ignored. On the other hand, some probability has to be given to a scenario of lower growth related to the ongoing pandemic which would lead to lower yields.

UK central bank less calm

In the UK, the Bank of England (BoE) seems to support a faster start to the normalisation phase. As explained in our UK macro outlook, inflation in the UK has reached record highs and is expected to surpass 4% in the next few months. On the back of a determined BoE, the market has started to price in a rate hike this year, with an additional 80-100bp increase in the base rate by the end of 2022.

Breakeven inflation rates price in an average retail price index rate of around 4% over the next 10 years, a level last seen in 1996, implying an extended period of excessive inflation. When considering that long-term inflation has been between 2.4% and 3.2% in the past 10 years, this appears very aggressive in our view.

BoE: only one opportunity to fail

Finally, a faster-than-expected hiking cycle would likely be followed by an accelerated tapering of the quantitative easing programme. This, in turn, may coincide with large planned gilt issuance by the UK Treasury, and cause unnecessary supply overhang. The Bank of Japan and the ECB can testify that policy errors are almost impossible to reverse, and the BoE will probably think twice before entering onto too aggressive a rate-hike path.

A base rate around 1% by year end, as implied by the rates market, leaves room for disappointment in our view. As such, short-to-medium term rates seem to offer value, while the longer end is likely to be torn between the two forces (inflation and growth risk), causing UK yields to experience a wide trading range going into 2022.

Italian bonds with more support

The ECB and European rates seem to feel the least pressure. While the deposit rate should remain unchanged, most of the discussion is likely to revolve around the format of a new asset purchase programme succeeding the current PEPP (pandemic emergency purchase programme) and APP (asset purchase programme).

According to reports, the new programme need not be bound to allocation keys. Instead, it may be designed to accommodate smaller and more indebted countries. At least from a monetary aspect this should provide support for spreads of peripheral countries like Italy or Portugal. As such, bonds from these countries may offer some value in an otherwise ultra-low yield environment.

Which bonds defy inflation

We often get asked which fixed income sub-asset class performs well during periods of higher inflation and higher trending yields. Historically, two bond segments have provided more stable performance against this backdrop: Inflation-linked bonds and high yield.

Inflation-linked bonds are expensive

Although they eliminate the inflation component, “linkers” would be less effective in a situation where an increase in yield rise would be not induced by higher real yields, just like during the 2013 Fed tapering process.

In addition, the inflation protection comes at a cost in the form of the breakeven yield which, as discussed above, is already well over 4% in the UK. As such, linkers would only be worthwhile if inflation stays durably above 4%, or if “stagflation” materialises.

High yield bonds

Spreads of high yield bonds from developed and emerging markets tend to perform well in a moderate growth environment with higher trending inflation. This is because high yield commodity producers and issuers can push through higher prices to consumers. While high yield bond spreads and CPI have often been negatively correlated, this is not always the case. Indeed, debt ratios, default rates, spread levels, and market yields can all decisively influence subsequent spread performance.

Spreads passed the best times already

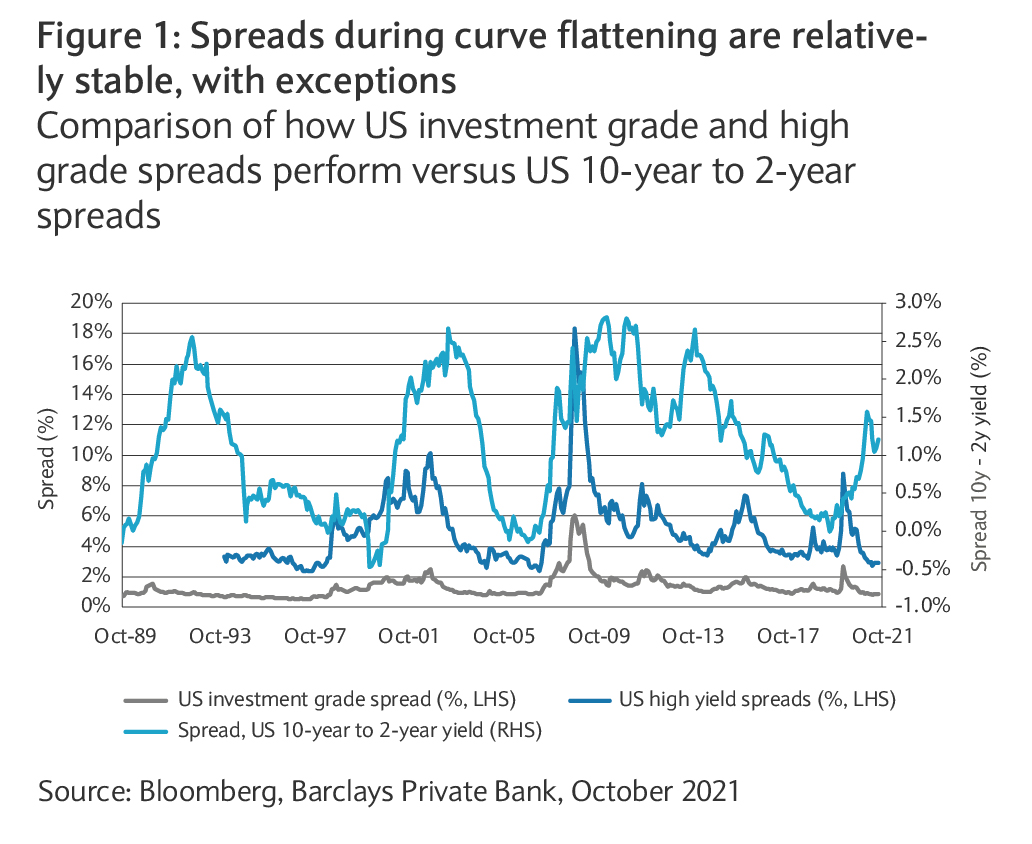

The current phase of economic recovery, lower trending default rates and accommodative monetary policies have built a solid backdrop for spreads to compress further. But at current levels (below 285 basis points (bp) in the US high yield market and 300bp in the emerging markets), spreads leave only limited room for substantial compression, in our view. This is also confirmed by past performance, according to the shape of the yield curve.

In addition, history shows that the bulk of the spread compression usually happens before the curve starts to flatten (see figure 1). They then remain relatively stable until the curve starts steepening, again at which point spreads typically widen.

Higher leverage acceptable…for now

Although the pandemic has led to a substantial increase in debt levels (the average net leverage ratio for US investment grade is 2.1 times, compared with 1.5 times 10 years ago), leverage isn’t much of a problem, for now.

As we discussed in October’s Market Perspectives, corporate behaviour is most relevant here. It’s only if companies exploit the low interest rate environment by rewarding shareholders excessively or engage in excessively expensive M&A activities, that debt investors may start to demand a higher compensation in the form of higher spreads.

Another important factor remains the default cycle as spreads have often started to move when default rates bottomed out. According to the rating agency Moody’s, global high yield defaults should bottom out in mid-2022.

With all that in mind, we believe corporate bonds can outperform in 2022. But remaining imbalances warrant a more selective approach.

Our verdict

With rate hikes already largely priced in, medium-term bonds seem to offer the most value

Where does this leave bond investors in 2022? Higher rates, inflation, and possible imbalances in the credit market remain key challenges. With rate hikes already largely priced in, medium-term bonds seem to offer the most value.

Meanwhile, we would see any rates move beyond 2% in the US 10-year as unsustainable, and would consider such periods as opportunities to lock in rates.

We would refrain from chasing yield using high beta issuers. Instead, we would stick to a more conservative and selective strategy especially in high yield and emerging markets until spreads become attractive again.