International asset allocation has become a more popular way to try and boost performance, and add foreign currency exposure, over the last three decades. But what factors are worth considering when deciding whether to hedge foreign exchange risk?

Global multi-asset class portfolios provide exposure to growth, inflation, interest rates, credit, equities and commodities. By diversifying across asset classes and geographies, various risk premiums can be harvested.

However, investors should be mindful of the underlying risks and carefully tailor their portfolios to strike the right balance of performance and risk. Foreign exchange risk is particularly important when investing internationally.

First, depending on the hedging policy, adverse currency moves can be a drag on performance. Second, “spending” the risk budget on exchange rate risk can prohibit the taking of other, potentially more rewarding sources of risk. Therefore, understanding and appropriately managing this risk is crucial.

The rise of international asset allocation

More globalisation spurred the growth of international trade from the early 1990s, resulting in stronger economic interconnectedness, and creating new business opportunities in all industries. In parallel, technological progress was the key driver of the unprecedented rate of financial innovation over this period.

At the same time, international asset allocation emerged as a standard form of investment. Based on the International Monetary Fund’s coordinated portfolio investment survey data, the foreign investments in equities around the globe have increased almost six times between 2001 and 2020, to $29.4 trillion from $5.2 trillion. During the same period, there was a fourfold increase of foreign investments in debt securities, to $31.9 trillion from $7.5 trillion.

Furthermore, since the end of the Bretton Woods system and the removal of the gold standard in 1973, many countries have adopted the floating exchange rate regime. So it comes as no surprise that foreign exchange risk has become a critical component of international asset allocation.

To hedge or not to hedge

When considering the impact of currencies on portfolio performance and risk, it is critical to assess whether to hedge the currency exposure.

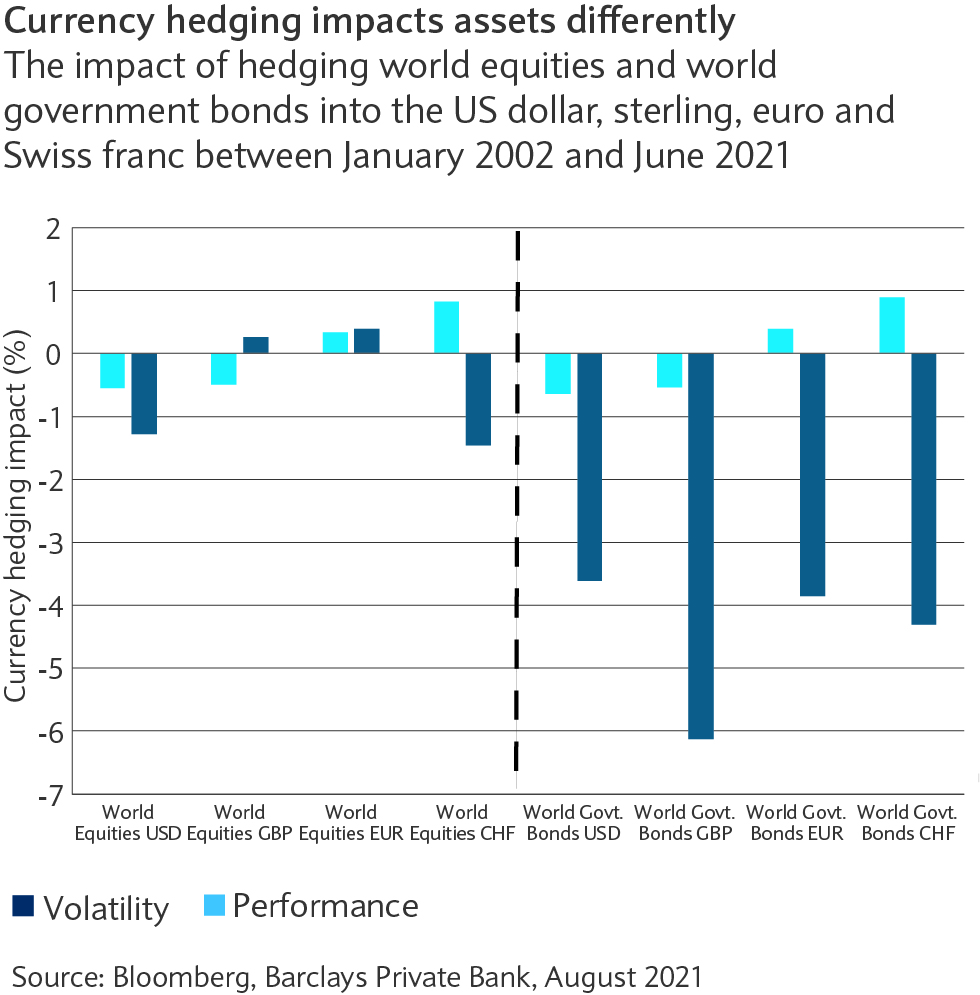

Hedging currency exposure impacts fixed income investments – the volatility is substantially lower if global government bonds are hedged (see chart). On the other hand, the effect of hedging on global equities is much lower and depends on the investor’s reference currency (for instance, hedging is usually preferable in US dollars and Swiss francs compared to euros and sterling).

Our results indicate that it is advisable to treat each asset class separately with regards to the currency hedging decision. The common practice is to fully hedge foreign fixed income investments and leave foreign equities unhedged.

Think strategically, act tactically

The hedging ratio rules defined above are usually applied over strategic investment horizons of five to ten years. In essence, this approach reflects the hedging demand solely based on risk considerations, averaged across different reference currencies. Its main purpose is to help investors to efficiently allocate risk across asset classes and meet their risk budget constraints.

However, foreign exchange markets are characterised by volatility outbursts and short-to-medium-term trends typically driven by macroeconomic and political factors. Such events can generate additional hedging or speculative currency demand that can be met by crafting tactical currency overlay strategies.

To design and implement currency hedging strategies, two points have to be addressed. First, which factors might explain exchange rate returns over short (tactical) and long-term (strategic) investment horizons? The answer depends on the nature of the underlying currencies (for instance, safe-haven versus pro-cyclical ones) and the macroeconomic outlook. Second, take into account hedging costs.

Inflation differentials drive FX returns

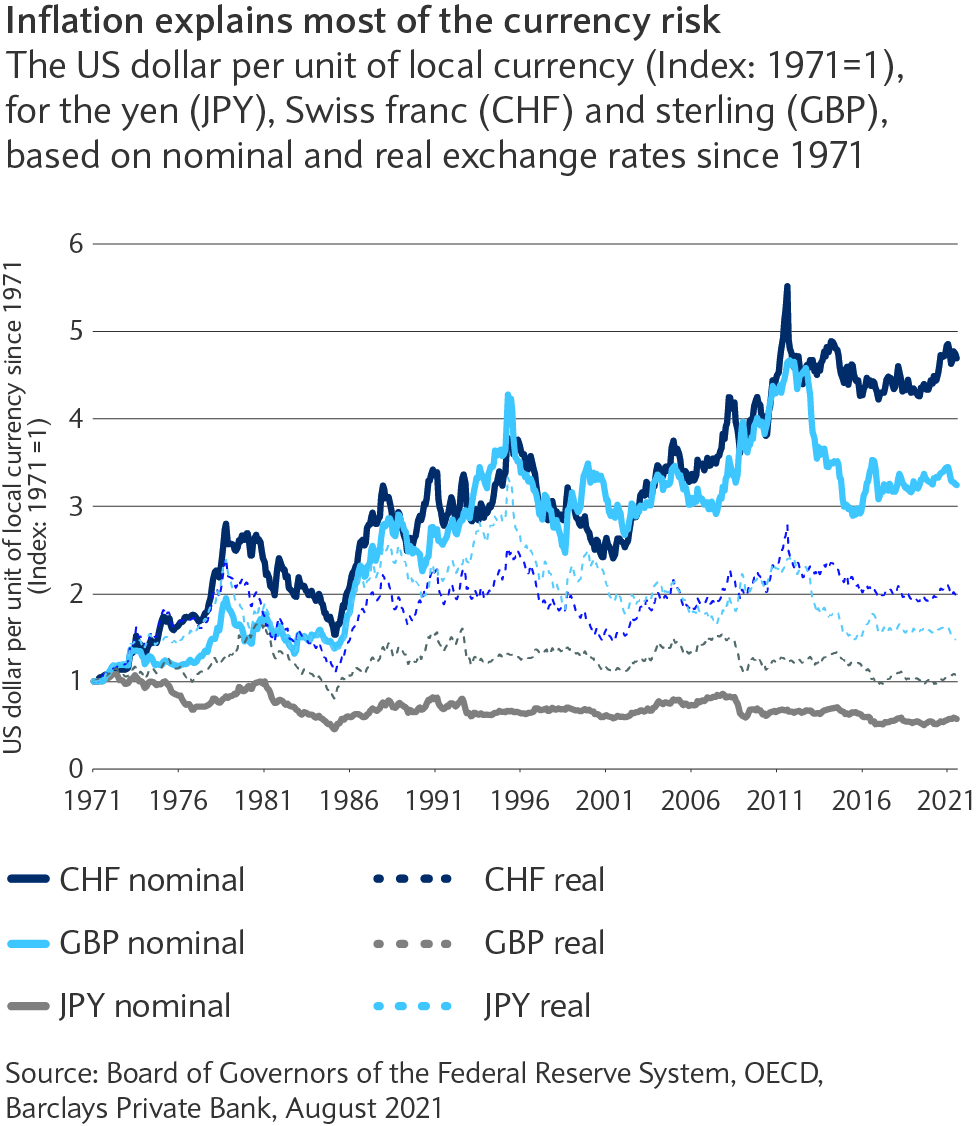

To understand the relation to the macroeconomic backdrop, the theory of relative purchasing power parity (PPP) is useful. The theory seeks to explain moves in exchange rates solely as a reflection of differences in price levels in the respective currency areas. Indeed, most of the persistent changes in nominal exchange rates seem to disappear when looking at real (inflation-adjusted) exchange rates (see chart).

However, relative PPP is far from perfect and some currencies still show trend-like behaviour (see the yen and Swiss franc, for example). Such deviations can be attributed to various economic fundamentals. In the case of these two currencies, persistent accumulation of net foreign assets seemingly accounts for some of the appreciation against the greenback in real terms.

Hedging, but at what cost

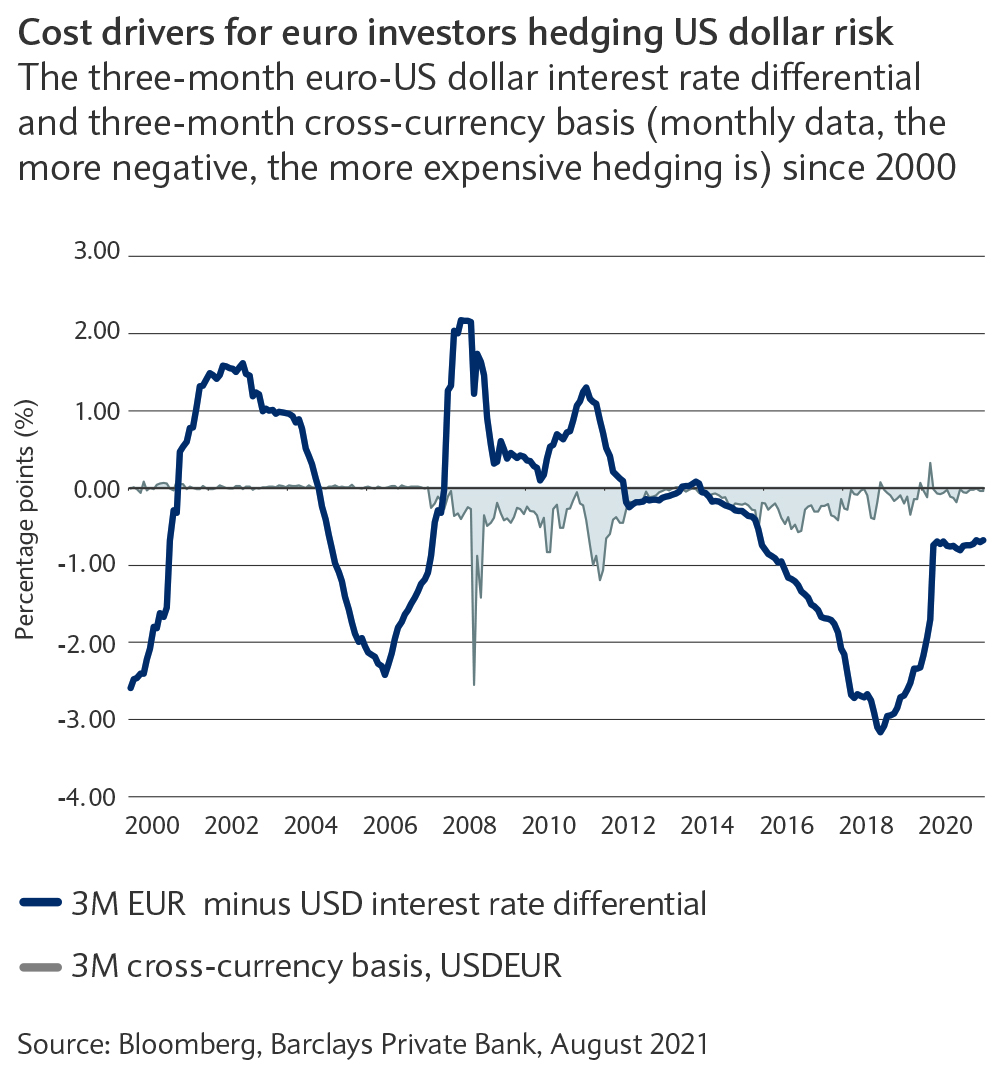

For a euro investor hedging a US dollar equity position, the lion’s share of the hedging cost can be attributed to the interest rate differential (see chart). In 2018, this was a costly endeavour due to the higher yield levels for the greenback needed to compensate the USD counterparty.

If everybody is trying to hedge the same risk, the price will probably go up. This notion of supply-demand imbalance is shown in the second cost-factor: the cross-currency basis. As a side note, this burst into life in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. During periods of extreme stress, the cross-currency basis can be substantial. Bid-ask spreads for all the hedging transactions form a third cost factor, which adds up over time, especially when using less liquid currencies.