A more hawkish Bank of England may imply higher UK rates. However, the prospect of much higher rates in the short term seems far from certain. That said, UK rates have scope to close the rate gap with US counterparts in the longer run, while corporate bonds offer an additional liquidity and credit premium.

BOE takes a more “hawkish” tone

The timing of when the Bank of England (BOE) starts lifting rates from their record low is a question on many investors’ minds. The central bank seemed to take a slightly more hawkish stance on the possibility of such rate hikes last month. But, will the stance be maintained at September’s BOE monetary policy meeting?

In August, the BOE signalled the possibility of earlier than previously envisaged rate hikes. Governor Andrew Bailey expected that annual UK inflation would peak at around 4% before moderating again. This in turn would justify monetary normalisation sooner than expected. Bailey stated: “Should the economy evolve broadly in line with the central projections...some modest tightening of monetary policy over the forecast period is likely to be necessary.”

Treading carefully

In judging interest rate policy, governor Bailey had long placed much emphasis on the monetary support and the downside risks to the UK economy. July’s higher-than-expected inflation figure of 2.0% after 2.5% in June, on a year-by-year comparison, had to be acknowledged and the inflation prints are likely to provide the central bank with more confidence in respect of when and how to “normalise” rates.

At the same time, Andrew Bailey sticks to his view of the transitory nature of recent inflation, in line with his counterparts Christine Lagarde at the European Central Bank (ECB) and Jerome Powell at the US Federal Reserve, and says that the central bank is not in a rush to lift rates. The ECB in 2011 demonstrated the dangers of a central bank prematurely hiking rates during a fragile recovery.

Scope for rate hikes seems limited

As a result of the BOE’s slightly more hawkish tone, the rate market pushed up by 15 basis points its expectations of a first rate hike by mid next year, based on forward-implied rates. That said, there seems no conviction for any hikes before 2024 thereafter.

Even the central bank’s own inflation forecast would not justify rate hikes beyond 0.5% before 2024. After peaking at 4% in 2021 the central bank expects inflation to moderate to 2.1% in 2022 and fall back below its own 2% inflation target by 2023. Hardly a backdrop for rate normalisation.

It seems too soon to tell whether the higher inflation seen in recent months is part of the transitory environment or a persistent trend. Like in the US (as mentioned in June’s Market Perspectives), the evolution of inflation in this cycle is likely to start with the base effects (higher rates due to the lower price levels seen a year ago at that stage of the pandemic) followed by pent-up demand and bottlenecks (as economies catch up with trend growth).

While a more prolonged economic upswing may add to additional inflationary pressures, the state of the recovery is still too early and uncertainties around any pandemic-related setbacks remain prevalent. It seems more likely that the BOE will need to adjust the neutral rate of inflation, or the interest rate thought to be needed so the economy can operate at full employment while keeping inflation at its target rate, to compensate for this uncertainty.

Opening the door for tapering

The uncertainty around economic prospects and inflation is one of the main reasons why the BOE has lowered the threshold level from which the central bank is mandated to taper the asset-purchase programme to 0.5% from 1.5%.

Rates of 1.5%, for now at least, seem out of reach and the central bank needed to make this adjustment if it ever wants to start normalising its balance sheet. Besides, BOE members like Michael Saunders and Dave Ramsden have been in favour of an earlier cut in asset purchases for some time now.

Steepening unlikely

If the BOE still keeps policy rates very low while giving itself more freedom to reduce the balance sheet, it may be argued that the rate curve will steepen from here. While higher volatility is a possibility, a substantially steeper curve seems unlikely in our view. Governor Bailey has emphasised that in the first phase of any asset-purchase tapering, the central bank would not sell any bonds but let them mature and not reinvest the proceeds received.

UK bond yields: playing catch up with the US

UK rates at the long end are likely to be impacted by the global backdrop as seen in the recent past. In addition, the correlation between the US 10-year yield and UK gilt yields has generally been quite high compared with other developed market rates in the past. The exception was 2016, when US rates surged on the back of the “Trump reflation policy”, or policies from the former president aimed at boosting US growth and risking lifting domestic inflation, while UK gilt yields were capped by Brexit uncertainties.

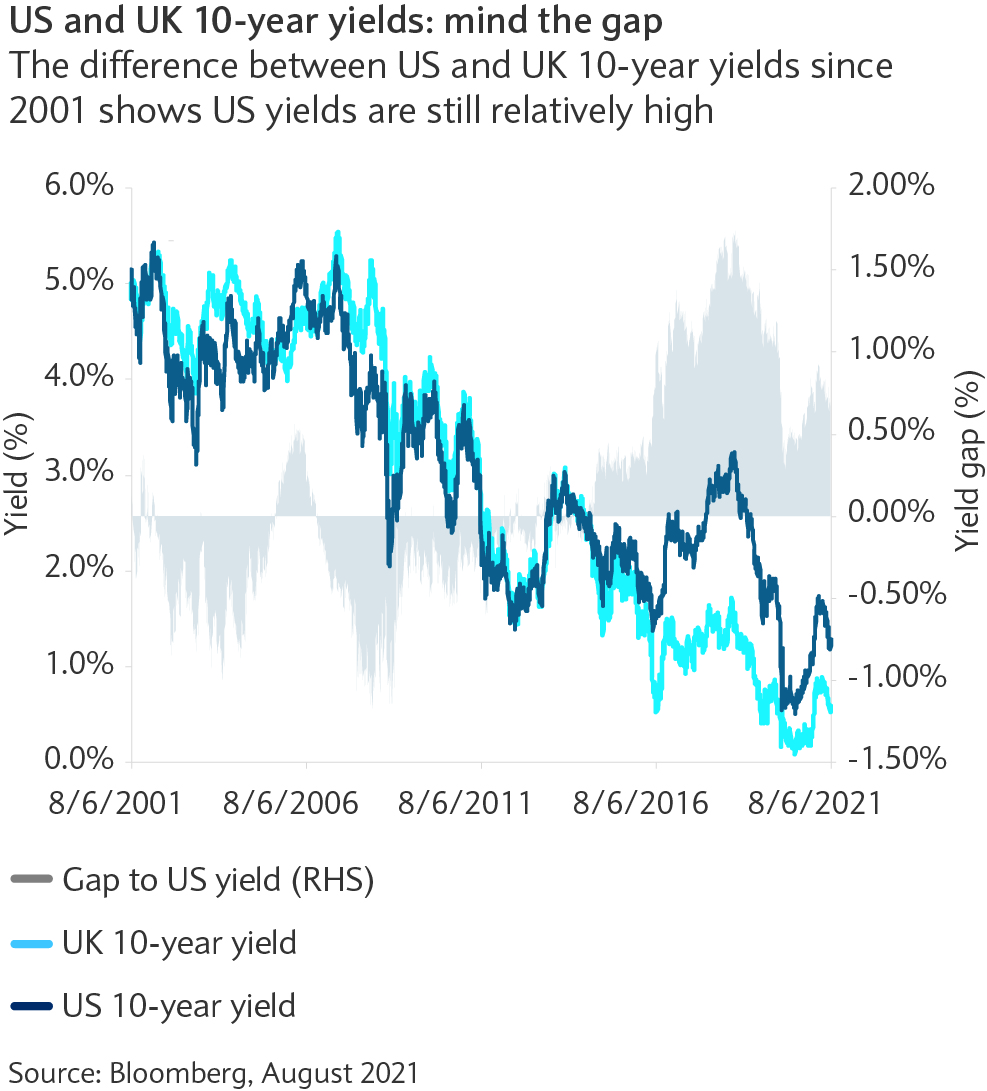

The yield gap opened between US and UK 10-year bonds in 2016 that peaked at 1.6% in August 2018 and now stands at around 0.7% (see chart). US yields have been higher than UK equivalents for the longest period for over 30 years.

Should elevated inflation persist in the UK it is likely that this gap would close significantly, if not disappear.

Credit and liquidity premium

Like in most regions, UK credit spreads seem to have reached their lows and in the case of high yield spreads have started to widen slightly. Less central bank accommodation in the future may result in more muted corporate bond performance. Still, carry returns seem to be an efficient way to gain yield as opposed to taking on longer duration.

UK spreads today, as in the past, trade at a slight premium owing to the market being less liquid and smaller compared to US or European counterparts, which provides opportunities.