Periods of continued positive financial market returns can make investors uneasy and expect a correction to be imminent. But duration of time isn’t the driver of the market cycle, and history shows that this shouldn’t be a primary concern for investors.

The outlook for the world economy and financial markets looks far more positive than it did at the outset of the pandemic, if not as strong as it did a few months ago.

Global vaccination efforts have led to an opening in those clouds that cast a shadow across the world last year and markets remain relatively close to their highs.

While the calmer markets seen in recent months may be appreciated far more by investors than previous periods of turbulence, others may fear that crosswinds are due.

It can be uncomfortable to be invested when markets are in a period of sustained positive returns, unhindered by substantial drawdowns and hitting record highs. A correction can feel imminent. Why?

The gambler’s fallacy

The gambler’s fallacy is a situation when we believe the likelihood of an event occurring is influenced by previous event outcomes. The market might feel due a correction because it has been rallying for long enough.

In the same way that a roulette wheel doesn’t have to land on red on the next spin because the last few have all been black, the market doesn’t have to correct simply because of a long rally.

What governs the market cycle?

Talking about a market cycle implies a cyclicality in the market; that the market will go through periods of expansion and contraction with regularity. The predictable cyclicality of the market can apply well at certain times, such as when a speculative bubble gives way to a crash.

However, expecting the market to correct simply because it has rallied beyond its historical average is the gambler’s fallacy.

Expecting the market to correct simply because it has rallied beyond its historical average is the gambler’s fallacy

It is important to reflect on what drives economic growth, expectations of which in turn drive financial market growth. The engines of economic growth and strong market performance will not stop functioning simply because they have been running smoothly and without interruption for an extended period.

Growth is the norm

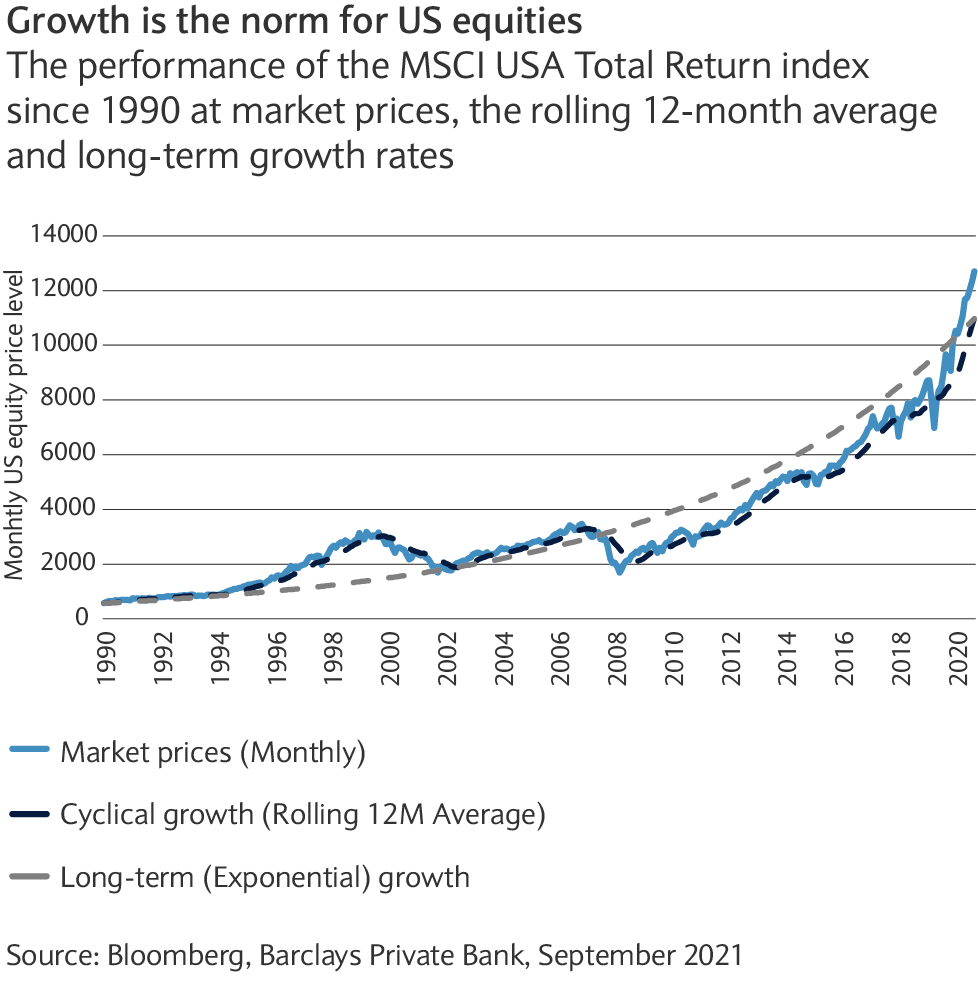

While past performance is no indicator of future performance, the historical performance of US equities provides a guide for nervous investors.

- Growth is the norm and not the exception (see chart): Examining US equity market levels shows a steady upward trend since 1990.

- Periods of positive returns are more frequent and last longer (see chart below): Examining monthly performance since 1990, we see positive monthly returns occur two-thirds of the time and that the average duration of months of consecutively positive returns are longer than those of negative ones (approximately twice as long).

Furthermore, the maximum length of a string of consecutive up markets is three-times as long as that of down markets. Up markets tend to trend month on month. As we’ve discussed before, history shows us that the longer the investor’s holding period, the higher the probability of a gain.

Up markets outperform down markets in terms of frequency and duration

Comparing monthly returns for the MSCI USA Total Return index by their average, largest, duration length and consecutive monthly runs for up and down markets.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average consecutive return

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Markets have continually reached at all-time highs (see chart on left): The chart shows that it is not uncommon for markets to reach all-time highs, which they have done once every three months on average between 1990 to 2021.

But there are developments I’m worried about

The previous charts may give investors useful historical context, though this may not be enough to soothe concerns about the current market. While there are risks that could affect market performance, it may be worth taking a broader view around the impact of events.

As we have discussed previously, a diversified portfolio can protect an investor from the impact of events in different parts of the market. Additionally, in investing, as with life in general, too much weight can be placed on potential negative risks that never actually materialise. In the absence of a crystal ball, investors may be better served by taking cues from history.

There is never a perfect time to invest

The risk of events occurring when least expected that might affect the success of your investments always looms on the horizon.

A first step to addressing the fear of such outcomes is to rationally assess them with an advisor and assign likelihoods to them and their likely impact on your portfolio. This may quickly rule out concerns that are unlikely to be material enough to stop you from reaching your goals.

By identifying scenarios that may require more attention, portfolios can be adequately positioned to protect yourself in the case that those risks do materialise.

The best way to do that is to adequately diversify a portfolio.

It is not a requirement for long-term investment success for an investor to have high conviction views about all market events. By diversifying a portfolio, you don’t have to. A portfolio that is well diversified will at times have assets which are performing less well than others, however it is when bad times occur that the value of these assets is realised.

One cannot rule out an event which takes down the entire market, like the pandemic, but financial markets are resilient and it takes an event of serious proportions to do so.

An investor of course will not want to invest when such an event is imminent, but their realisation and their timing can be very difficult to predict. With this in mind, it is our belief that getting and staying invested remains the best option for investors looking to reach their goals over the long term.

It is our belief that getting and staying invested remains the best option for investors looking to reach their goals over the long term