Market Perspectives April 2023

Welcome to our April edition of “Market Perspectives”, the monthly investment strategy update from Barclays Private Bank.

Fixed income

03 April 2023

Michel Vernier, CFA, London UK, Head of Fixed Income Strategy

Last month, was eventful for the bond market. The US 2-year Treasury yield first climbed to a record 5.1% on 8 March, the highest level since 2007, as markets reacted to tight job market data and a hawkish sounding US Federal Reserve (Fed) chair, Jerome Powell, at the US congress hearing. At its peak, the rate market priced in a terminal rate for the US Fed’s policy rate of almost 5.75%.

Between 9th and 11th March, however, such hawkish fears appeared to have been wiped out, triggered by the troubles facing Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) in the US as well as heightened credit concerns, and finally the takeover of Credit Suisse by UBS in Europe.

The US 2-year Treasury yield then recorded another record on 15 March: the largest one-day drop since the Volcker period, named after former Fed chair Paul Volcker, in the early 1980s. The forward rate market dropped the peak policy rate by 100 basis points (bp) to 4.9% during the day.

The magnitude of the move can also be witnessed in the headline measure for interest rate volatility, as measured by the Merrill Lynch Options Volatility Index, or “MOVE”, which jumped to the highest level seen in the aftermath of the global financial crisis in 2009 (see chart).

Almost a year to the day since the Fed’s initial rate hike in 2022, the focus has shifted for the first time from inflation to financial conditions, from macro to micro, from price risk to credit risk. SVB, a US bank that targeted the tech sector, had to realise large capital losses on its Treasury assets as it dealt with a surge in deposit withdrawals from clients.

And while sentiment was already very negative, funding spreads of the Credit Suisse blew out to distressed levels on the back of a lack of profitability and investor trust.

Central banks were quick to act with liquidity facilities and, in the case of Credit Suisse, even with an orchestrated merger (or takeover) with UBS. But question marks remain: are higher interest rates finally taking their toll? And might a banking or credit crisis be around the corner?

The reasons for the collapse of SVB and Credit Suisse, and more importantly the trigger, were different in nature in both cases, and worries over any large credit crisis seem to be overstated. While one bank’s demise was caused by its excessive growth strategy, apparent lack of risk management and its over-reliance on one sector, the others was sparked by a lack of investor patience with regards to its long-term profitability.

Still, the heightened uncertainty comes at a time of higher interest rates, a shift that had already caught out the UK pension industry’s use of liability-driven investments in October, when only a central bank intervention averted greater damage in the domestic bond market and pensions sector.

Not only have higher interest rates exposed the mark-to-market value of assets and liabilities on balance sheets, but they have also lowered the barrier for repatriating assets to safe-havens in times of extreme uncertainty.

The good news is that a liquidity mismatch as seen within some domestic US banks and some UK pension funds this time can be mitigated relatively easily by central bank intervention as opposed to a fully blown insolvency crisis, as witnessed in 2008.

Some of the dangers of higher interest rates and tighter financial conditions were explored in the recent articles 'The road to normalisation for bond investors?' and 'The dangers of complacency'.

The risk and effects of tighter financial conditions was, and still is, a reason for a cautious stance towards high yield bonds: simply said, after all boats were stranded on low interest-rate ground for a decade, they must prove that they can float again when the interest-rate tide comes in again.

Some boats, or business models, were built during the low tide and may not be waterproof. So, contrary to the old saying, not all boats will be lifted with the tide. But, equally, this does not mean that the world is in a full-blown crisis or heading towards one.

Clearly, the recent level of uncertainty should serve as a reminder that financial conditions have become more restrictive, not as a side-effect but because it is ultimately the intention of the central banks as they look to curtail demand in the hope of moderating inflation.

Given current circumstances, the article now turns to look at the credit cycle. The credit cycle is a concept that was most prominently outlined by US economist Hyman Minsky. Credit cycles describe the level of access people and businesses have to credit, which in turn impacts asset price levels.

The stage of a credit cycle is typically identified by factors related to the business cycle, as well as corporate fundamentals and financial risk taking.

The four stages of a typical credit cycle are: expansion, downturn, credit repair and recovery. The global financial crisis is the most obvious example of a downturn or “Minsky moment” in recent decades, while the US saving and loan banking crisis in the late 1980s should also be borne in mind, given events in March.

Outside of a large downturn, it is fair to say that most of the time, as today, credit cycles are in an expansionary phase. The challenge is to identify whether it’s a later or earlier stage within the expansion. But as US economist Kenneth Rogoff pointed out in From financial crash to debt crisis [PDF, 334KB], cycles can last for decades and should not be confused with business cycles (although they can coincide).

Given that the cost of credit has risen substantially over the past 12 months, it is reasonable to be vigilant and monitor developments. For credit investors, specifically buy-and-hold ones, the most important factor to watch is default rates.

Default rates among speculative bonds have already picked up globally, rising to 4.3% in 2022 from a very low level of 1.8%, and are expected to increase towards 4.4% in 2023, according to rating agency Moody’s (the rather limited increase is a result of defaulted Russian bonds dropping out of the rolling 12-month statistic). This would still be well below the peak in default rates seen in the COVID-19 pandemic of 7%, according to Moody’s. Thereafter the rate is expected to consolidate according to the rating agency.

While a large increase of default rates seems less likely, there still appears to be some upside risk. A scenario in which default rates increase towards 5%, or slightly more, and potentially stay at higher levels for a longer period, seems likely.

Unlike during the recoveries following the pandemic or global financial crisis, the ability of governments and central banks to provide large-scale accommodation is limited this time, as significant rate cuts would undermine efforts to tame inflation.

The 25bp hike by the US Federal Reserve and Bank of England, as well as the European Central Bank’s 50bp rate move, in March, despite the turmoil in financial markets, seems to amplify policymakers’ focus on tackling inflation.

As such, more vulnerable credits will face tighter financial conditions on their own. Indeed, US speculative default rates have generally risen in hiking cycles, with the exception of a period between 2015 and 2016; another sign that default rates will probably head higher.

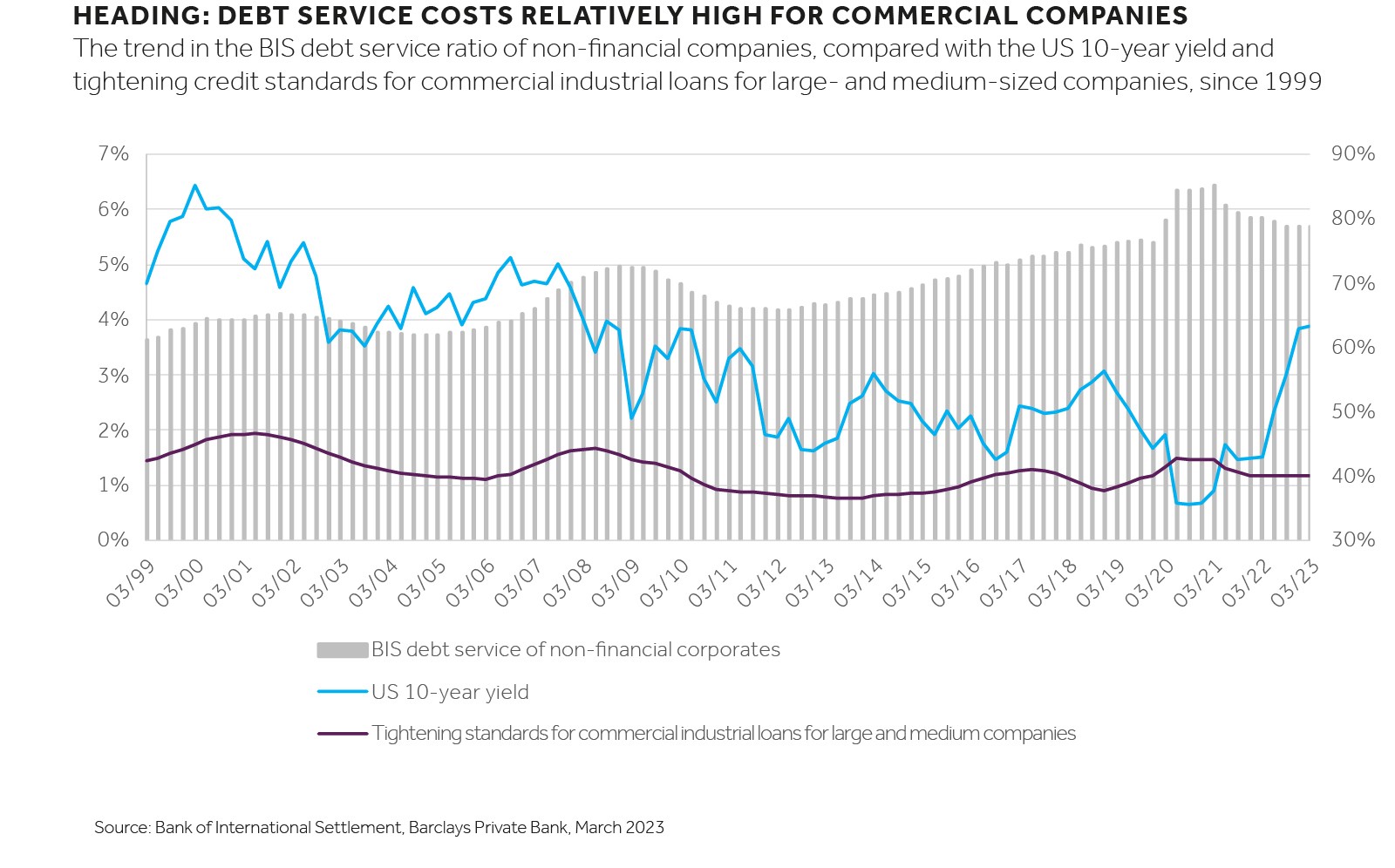

Recent events within the US banking sector and Europe may cause financial conditions to tighten further with access to credit from banks becoming more restrictive. The diffusion index of tightening standards for commercial industrial loans for large and medium companies supports this view (see chart).

The index shows the level of tightness in credit conditions indicated by domestic respondents standing at 44.8%. This might not be as tight as seen during the pandemic in 2020, but a level of over 40% was only surpassed four times in the last 35 years (in the late 1980s, 2001, 2008 and 2020). That said, conditions may tighten in coming months.

Most companies have termed out their funding during the depressed interest rate levels seen in 2020 and 2021. But the tide seems to have turned. Should interest rates stay higher for some time, funding costs are likely to increase.

At the same time, leverage, as a percentage of US gross domestic product, for example, has retreated but is high by historical standards. In the absence of a deleveraging process, the higher level of leverage might amplify the increase in debt service costs expected in coming months and years.

Service costs (see chart), as a measure of the interest coverage ratio, remain low at companies, but have started to increase, especially among high yield bond issuers. US interest expenses increased by 5.6% in the fourth quarter of 2022, and by almost 11% on a year-on-year basis, according to Bloomberg. If the trend continues, lower earnings could exacerbate the situation among high yield issuers.

Credit cycles can span over years or decades and as such we would not go as far as predicting an inflection point at this stage. But the headwinds for credit spreads have risen of late, which justifies a vigilant approach. US investment grade corporate spreads have already surged to 160bp from a recent low at 115bp.

Investment grade spreads have predominantly been impacted by bank bonds and remain elevated for now. But given that the risk of a full-blown banking crisis seems low, spread volatility may remain limited within the investment grade segment. Furthermore, the general trend of corporate bond investment grade yields appears to be towards being lower, given inferior rates over the medium term.

High yield bond spreads have surged from 390bp to 510bp of late and seem to better reflect the inherent risk of the bonds at this stage. But lower growth and tighter financial conditions are likely to hurt the most leveraged issuers and further repricing of spreads is likely.

The upper limit of the recent range in spreads is around 600bp, which seems to represent a minimum level of likely outcomes in the short term. However, spread levels of over 1,000bp, as seen during the pandemic, seem far less likely.

The average yield of US high yield bonds has surged to 9% from just below 8% in recent weeks, which justify some selectively repositioning bond portfolios. That said, today’s highly uncertain backdrop might not justify a very large exposure to the asset class.

As mentioned before, bond market volatility, be it on the rates level or spread levels, is likely to remain fairly elevated for the remainder of 2023.

The good news is that volatility creates opportunities to lock in yields. The window to do so within investment grade debt may close within the next few months as yields trend lower. Due to the higher dependency on spreads and the related volatility, opportunities to add more exposure to high yield bonds may emerge. For now, a selective approach seems warranted.

Welcome to our April edition of “Market Perspectives”, the monthly investment strategy update from Barclays Private Bank.

This communication is general in nature and provided for information/educational purposes only. It does not take into account any specific investment objectives, the financial situation or particular needs of any particular person. It not intended for distribution, publication, or use in any jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, or use would be unlawful, nor is it aimed at any person or entity to whom it would be unlawful for them to access.

This communication has been prepared by Barclays Private Bank (Barclays) and references to Barclays includes any entity within the Barclays group of companies.

This communication:

(i) is not research nor a product of the Barclays Research department. Any views expressed in these materials may differ from those of the Barclays Research department. All opinions and estimates are given as of the date of the materials and are subject to change. Barclays is not obliged to inform recipients of these materials of any change to such opinions or estimates;

(ii) is not an offer, an invitation or a recommendation to enter into any product or service and does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities, investment advice or a personal recommendation;

(iii) is confidential and no part may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted without the prior written permission of Barclays; and

(iv) has not been reviewed or approved by any regulatory authority.

Any past or simulated past performance including back-testing, modelling or scenario analysis, or future projections contained in this communication is no indication as to future performance. No representation is made as to the accuracy of the assumptions made in this communication, or completeness of, any modelling, scenario analysis or back-testing. The value of any investment may also fluctuate as a result of market changes.

Where information in this communication has been obtained from third party sources, we believe those sources to be reliable but we do not guarantee the information’s accuracy and you should note that it may be incomplete or condensed.

Neither Barclays nor any of its directors, officers, employees, representatives or agents, accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct, indirect or consequential losses (in contract, tort or otherwise) arising from the use of this communication or its contents or reliance on the information contained herein, except to the extent this would be prohibited by law or regulation.