Aggressive central banks hiking and a worsening outlook for the global economy suggests that a period of lower inflation is on the horizon. But the path to moderation is likely to remain choppy. How do inflation-linked bonds stand out at times like these?

Many central banks have picked up the pace of interest rate hikes significantly during the last two months: 50 basis points (bp) represents the absolute minimum these days it seems.

The Bank of England (BoE) hiked by 50bp, while the European Central Bank (ECB) and the US Federal Reserve (Fed) lifted rates by 75bp at their September meetings. Taken together, the three of them have hiked by a whopping 350bp since June.

The three central banks are determined to fight record inflation. While the backdrop for all three economic areas differs, to some extent time is money. And the cost of not acting forcefully and swiftly is believed to be too high.

No pain, no gain

The Fed leads the hiking cycle charge among the major central banks and does not seem to be shying away from greater growth repercussions. “No one knows whether this process will lead to a recession or if so, how significant that recession would be,” Fed chair Jerome Powell told reporters during his FOMC press conference in September. He added: “We have got to get inflation behind us. I wish there were a painless way to do that. There isn’t.”

The FOMC members project a rate of 4.6% (median) by the first quarter of next year. “The path that we actually execute will be enough”, he said when referring to the task of bringing inflation back towards the 2% target (a long way from here).

Fed’s rate projection seems realistic

The rate market won’t dare challenge the central bank’s policy rate path and prices in a peak rate close to the Fed’s “dot-plot” projection, at around 4.6% (mid-point) early next year. With such a move, the Fed’s forecast for a moderation in inflation towards 3.1% by the end of next year seems realistic, while the risk of stickier inflation remains.

Base effects, diminishing pressure from pandemic-related components like cars and airfares, but also lower trending healthcare insurance costs, as well as a cooling housing market, point to weaker price growth. Until then, the core underlying (longer-lasting) trend, as reported by recent inflation prints, seems firmly up. Meanwhile, food and energy costs remain a risk for the trend of moderation.

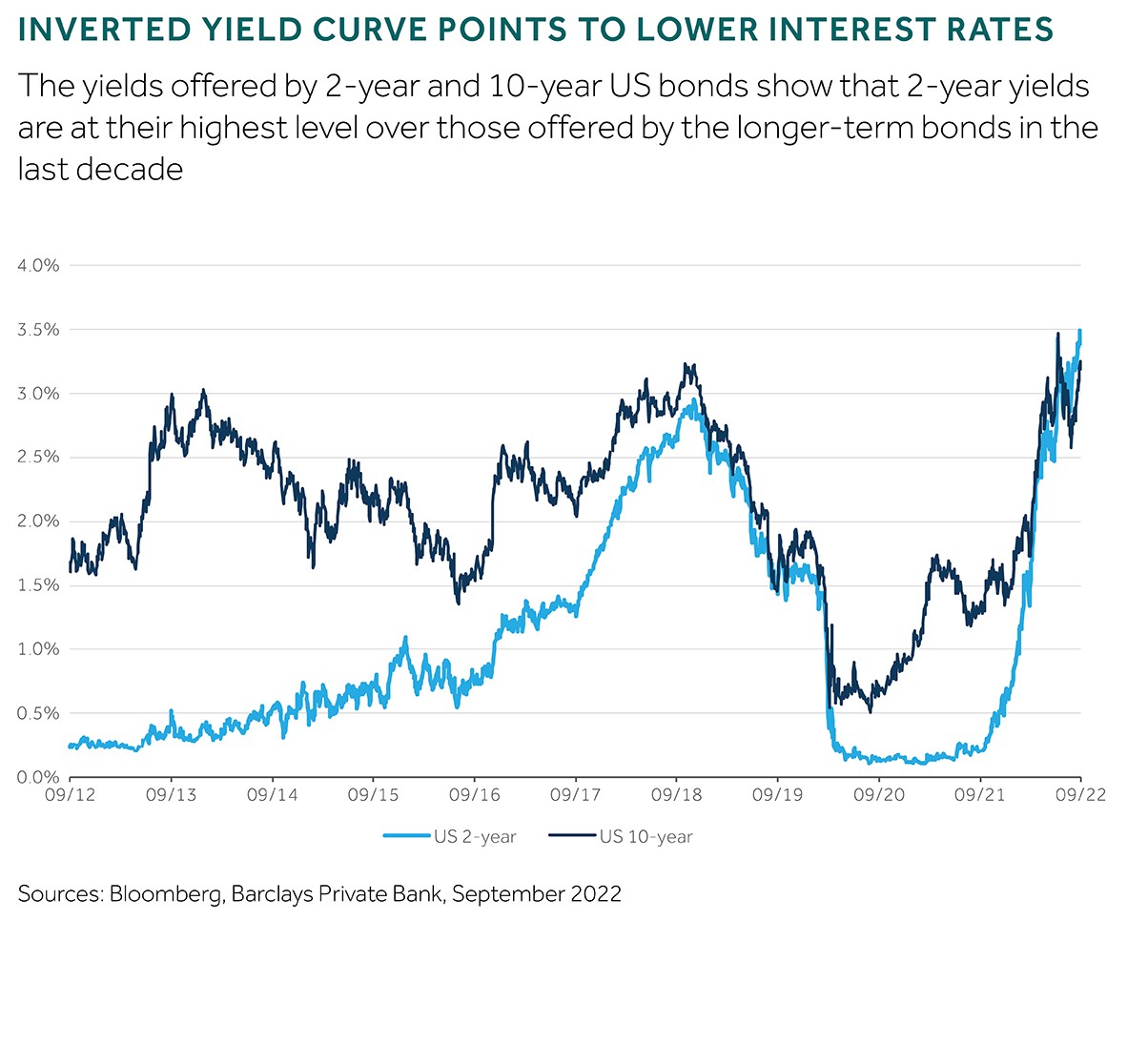

While the short end of the curve tries to calibrate towards the possible peak in rates, the long end is already looking beyond the period of peak inflation. This should also explain why bond investors would settle for the lower yields that longer-dated bonds offer over shorter-dated bonds. Over a five-year period, for example, it appears very likely that policy rates in any of the bond markets may fall, especially in a recessionary environment.

Cash rates high, for now

Cash rates, as implied by 2-year bond yields, may be on the up for now. However, over a longer period yields are likely to adjust downwards again. As such, cash is unlikely to perform better than what current long-end yields suggest, in our view (see chart).