Global Outlook 2023

As investors near the end of a tough year, full of twists and turns, our bumper Outlook 2023 takes a look at prospects for financial markets next year.

Michel Vernier, London UK, Head of Fixed Income Strategy

After another challenging year for bond investors, the pace and path of interest rates and inflation will be vital for prospects in 2023. Yield opportunities have already emerged and investment grade corporate bonds may offer the tastiest pickings.

Bonds have had their worst year this century as central banks finally realised that the surge in inflation was not “transitory”. Their U-turn to a more aggressive, determined approach to fighting inflation saw cumulative rate hikes of 850 basis points (bp) by the US Federal Reserve (Fed), the European Central Bank (ECB), and Bank of England (BoE). With the prospect of more “jumbo” moves to come, the short end of the rate curve has reached levels not seen since 2007.

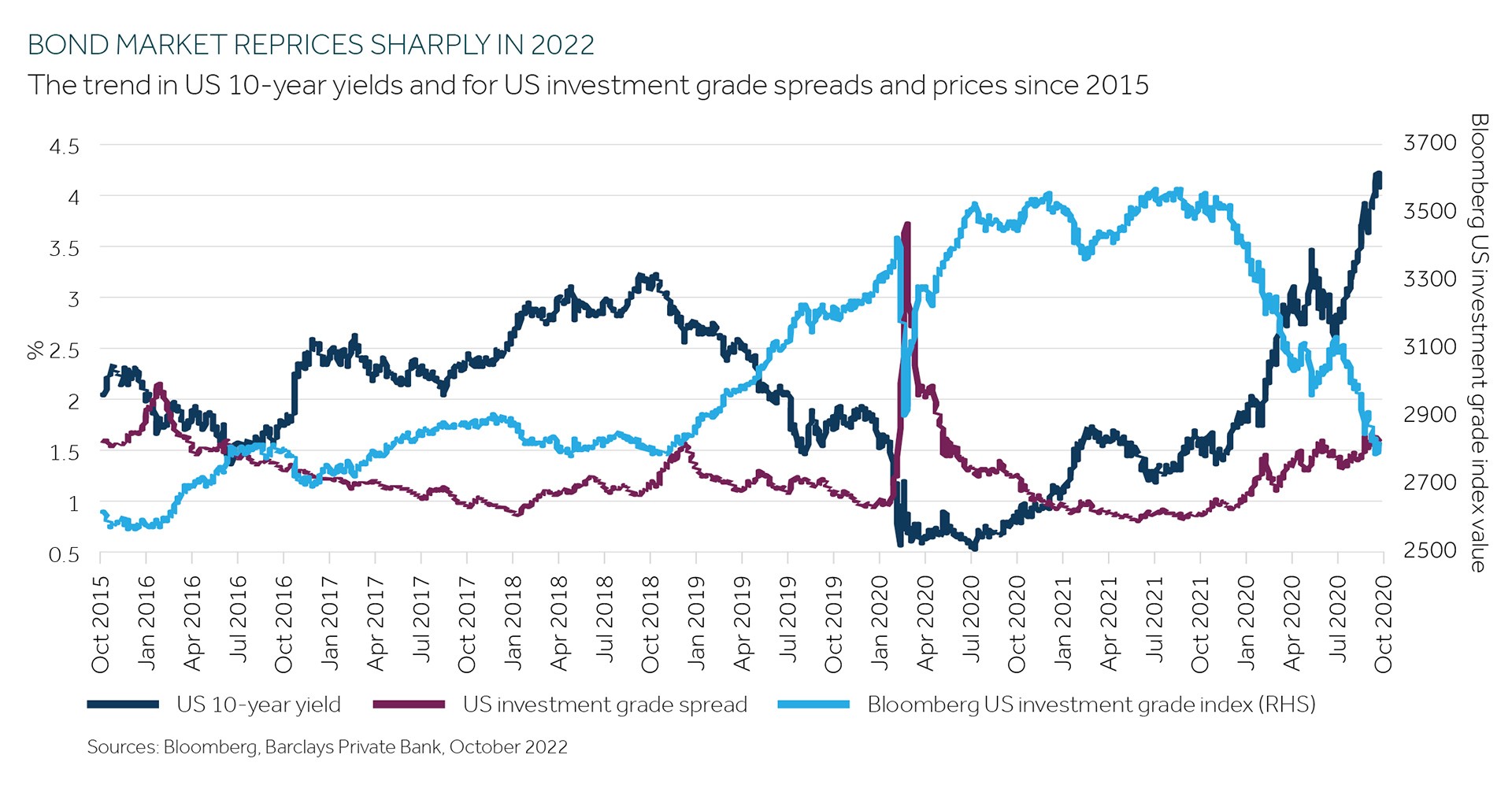

The vacuum created by the short end has pushed long-end yields higher, albeit to a lesser degree given that the long end of the curve tries to anticipate lower yields once peak policy rates have been reached (rightly or wrongly). Regardless of the shape of the curve, higher rates sparked a substantial repricing of the bond market and significant losses for bond holders (see chart).

However, mark-to-market losses on fixed income holdings in 2022 will only be realised if these are sold, or if we assume that many bonds default, of course. If held to maturity, the capital and the yield stated at purchase (even if negative, as seen in Europe) would still be realised.

With hindsight, the yield offered for 2-year US Treasuries during 2020 and 2021, at around 0.25%, was insufficient given the subsequent inflationary pressures. The question for bond investors is not necessarily whether fixed income markets are prone to further mark-to-mark losses, but if current yields appropriately price for future inflationary pressures and general risks. By focusing on this outcome, rather than trying to catch peak yield levels at the point of maximum losses, a more sustainable result can be achieved.

The first factor to watch is the path for inflation and the likely response from the central bank. This is what will drive short-end yields, ultimately (and with them the rest of the bond curve).

Admittedly, over the year, we and most of the Street have revised peak base rates up gradually. This reflected a re-assessment of inflationary pressures and central banks’ response, especially the Fed, as well as the economic consequences of the war in Ukraine.

Since the release of the Fed’s updated “dot-plot” projection in September, it seems that the rate market and the US central bank are in broad agreement on a terminal peak rate of around 5.25% being reached by the middle of 2023.

Fed chair Jerome Powell keeps reiterating that, at least for now, economic repercussions are the cost of the tightening policy: “We have got to get inflation behind us. I wish there were a painless way to do that. There isn’t.” As such, the Fed is unlikely to hesitate in lifting rates further in the absence of a sustainable moderation in inflation.

The US central bank expects its favoured inflation measure, the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) rate, currently at 4.9%, to reach its target by 2024. This seems optimistic, given the pressure building in core service inflation, a trend which is usually sticky. This, in turn, suggests that the risk of a higher terminal rate is skewed to the upside.

Still, as outlined in our macro section, a moderation of inflation is likely to be around the corner. Disinflationary trends in car prices, healthcare costs, and shelter (living) expenses along with the prospect of much lower growth, potentially a recession, suggest the worst (on the inflation front) is almost over.

The crucial question for next year remains how fast will inflation moderate? Here, current market pricing may not fully reflect the potential for surprises. At the same time, we don’t believe the risk of an even higher peak in inflation and policy rates should be disregarded. Recent Fed commentary seems to suggest that this is one of the biggest risks to be managed.

The central bank has often pointed to the risk of easing rates too early. In 1974, the Fed started to lower peak policy rates of 12% only for inflation to flare up again.

With this in mind, it has used every opportunity to warn that higher rates are here to stay. By providing such advice, the policymakers hope to be able to reach a lower, but prolonged, level of peak inflation.

The bond market, meanwhile, seems to expect a different scenario, which appears optimistic on two levels. First, it does not price in the possibility of a higher peak in inflation. Second, the rate market anticipates rate cuts less than six months after the peak, something that we believe is not on the Fed’s agenda.

Of course, risk of a severe downturn remains, together with the possibility of a partial unwinding of the rate hikes. But to get there, we believe fed fund rates potentially need to peak even higher than is being priced in at the moment.

From a positioning point of view, this makes the short- to medium-term part of the curve the most attractive. Meanwhile, there seems a higher probability that the longer-end of the curve may reprice to the upside, acknowledging that rates can stay higher for longer. While the path from current inflation levels to 4% may be steep, it could take much longer to hit the 2% target subsequently.

With a possible peak in the terminal rate next year, and the Fed possibly refocusing more on financial conditions, we believe that opportunities at the longer end of the curve may emerge later next year. During past hiking cycles, including in the 1970s, the US 10-year rate usually peaked either at the moment short rates hit their top or slightly before, with the respective peak usually close to, or even below that seen in the policy rate.

In the UK, the yield curve will likely be affected by the path of the policy rate and bond supply dynamics. We expect the BoE to keep aggressively front-loading hikes next year. Governor Andrew Bailey said that “inflation hits the least-well-off the hardest, but if we don’t act to prevent inflation becoming persistent, the consequences later will be worse”.

But the market still seems to be focusing too much on the risk of higher rates. The former government’s unfunded fiscal plans unveiled in September led to a substantial repricing of the base rate to a peak of around 6%. Even after the reversal of the government measures in October, the curve still prices in a peak of around 4.65%.

The retail price inflation index may shrink to 4.5% by October next year, having hit 12.6% in September 2022 . This, together with the bleak growth outlook for the UK, may stop the BoE hiking to the level implied by the market.

Contrary to the US, we see the possibility of a lower-than-implied peak. This represents an attractive opportunity to lock-in yields at the short- and medium-part of the curve.

On the other hand, rate volatility at the long end will likely remain. A more substantial gilt supply – albeit lower than initially feared – will collide with the BoE’s quantitative tightening and active sale of sovereign bonds it carries on its balance sheet. This, together with the UK gilt market being comparatively small, creates fertile ground for more rate volatility going into 2023.

In Europe, policy rates of over 2.5% seem realistic, in our view, with the caveat that many supply-driven inflationary pressures cannot be addressed with higher rates. But, in addition to inflation dynamics, local investors may also focus on Italy, the largest bond market in the bloc. The country’s unsustainable and worsening debt to gross domestic product ratio (already over 150%) as well as the risk of increased tensions between the newly elected government and the EU, will likely result in continued pressure on Italian debt.

The ECB’s back-stop programme may well get tested should Italy’s bond market show more signs of distress. At higher spreads, and given the continued support for the country from the EU and ECB, renewed yield opportunities may emerge. In addition, peak investment grade bond yields usually coincide with that for rates, not necessarily the spreads (see September’s Catching peak bond yields).

Admittedly this was different during the pandemic crisis and the great financial crisis, but a credit crunch in the investment grade bond market looks less likely than it did back then. Leverage may have only moderately declined from the peak pandemic levels, but investment grade issuers, in particular, largely termed out their funding during the pandemic crisis. This should provide a buffer against rising interest rates.

Meanwhile, many bonds, especially European investment grade and UK corporate bonds, trade at spreads that are close to recessionary levels. While the risk is elevated, equally, the troubles sparked in the energy market in 2022 could be more manageable in the next six-to-12 months.

In the US, the average investment grade bond spread is around 50-100bp away from what might be described as recessionary levels. While investors could experience some short-term mark-to-market losses if yields were to jump above 7%, the segment’s average yield of 6% – which was last seen in 2009 – represents an attractive risk-reward for an investment of five or six years. After all, this is not too far off the long-term average return that the equity market promises.

The outlook for high yield seems cloudier, given that spreads contribute much to performance. And, apart from Europe, global high yield spread levels do not fully reflect the risk of higher rates, excessive inflation, and certainly not a recession.

Global default rates within the speculative grade market have so far been contained at around 2%. However, given the current macro backdrop, the risk is that this number rises. While higher-quality, BB-rated, debt may be more insulated (and offer very selective opportunities), the risk of spill over from the most leveraged and vulnerable issuers is uncomfortably high. A lower growth path, margin pressures, and higher funding costs suggested by the short-term funding profile, do not bode well for high yield issuers.

A common theme facing emerging market bond investors is the challenging backdrop created by a strong US dollar and higher USD rates. This has already led to significant outflows from this part of the bond market, as carry trades became increasingly less attractive.

Next year should bring similar challenges, as some emerging markets are faced with a worryingly weak currency already. Lower dollar reserves, with less headroom to counteract any further dollar-imported inflation, and limited fiscal leeway are also likely to pose a risk.

But, 2023 could be a turning point. If US policy rates peak, and if the market starts to price lower rates for 2024 or 2025, emerging market debt could stage a comeback. The timing may coincide with higher spreads, which would open carry opportunities. During the last 20 years, average yields of over 6-7% led to solid subsequent performance.

As outlined, the discussion around “peak-rate” will likely dominate the first half of 2023 and investors may have to face further mark-to-market losses in the short term. The biggest risk, in our view, is a longer-than-expected road to moderation and a period of prolonged higher yields. However, when one steps back and assesses the risks in light of current yields, opportunities become apparent. Fixed income, as an asset class, should not be ignored anymore.

As investors near the end of a tough year, full of twists and turns, our bumper Outlook 2023 takes a look at prospects for financial markets next year.

This communication is general in nature and provided for information/educational purposes only. It does not take into account any specific investment objectives, the financial situation or particular needs of any particular person. It not intended for distribution, publication, or use in any jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, or use would be unlawful, nor is it aimed at any person or entity to whom it would be unlawful for them to access.

This communication has been prepared by Barclays Private Bank (Barclays) and references to Barclays includes any entity within the Barclays group of companies.

This communication:

(i) is not research nor a product of the Barclays Research department. Any views expressed in these materials may differ from those of the Barclays Research department. All opinions and estimates are given as of the date of the materials and are subject to change. Barclays is not obliged to inform recipients of these materials of any change to such opinions or estimates;

(ii) is not an offer, an invitation or a recommendation to enter into any product or service and does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities, investment advice or a personal recommendation;

(iii) is confidential and no part may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted without the prior written permission of Barclays; and

(iv) has not been reviewed or approved by any regulatory authority.

Any past or simulated past performance including back-testing, modelling or scenario analysis, or future projections contained in this communication is no indication as to future performance. No representation is made as to the accuracy of the assumptions made in this communication, or completeness of, any modelling, scenario analysis or back-testing. The value of any investment may also fluctuate as a result of market changes.

Where information in this communication has been obtained from third party sources, we believe those sources to be reliable but we do not guarantee the information’s accuracy and you should note that it may be incomplete or condensed.

Neither Barclays nor any of its directors, officers, employees, representatives or agents, accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct, indirect or consequential losses (in contract, tort or otherwise) arising from the use of this communication or its contents or reliance on the information contained herein, except to the extent this would be prohibited by law or regulation.