Amid a storm of data on inflation, economic activity, and labour markets, it can be difficult to pinpoint one’s position or even ascertain the direction of travel. We discuss the importance of inflation anchoring and show how much it has loosened this year, as well as the potential implications for portfolios and the economy.

Analysis of inflation has been dominated by one topic over the last two decades: the ability of central banks to influence inflation using standard monetary policy tools, also referred to as the flatness of the so-called Phillips Curve.

After having been declared dead countless times, the Phillips Curve relationship, between the central bank policy rate and the inflation rate, was finally resurrected when the idea of time-varying degrees of inflation-expectation anchoring was added to the standard equation. This approach explains why monetary policy intervention at times had very little effect on inflation: the expectations were simply too well anchored.

This anchoring-induced slumber, of inflation, may have encouraged central banks to take actions that were not necessarily linked to their primary goal of price stability, such as saving equity markets (and banks), bailing out governments, and stimulating corporates through a worldwide pandemic.

In fact, in February 2021, US Federal Reserve (Fed) chair Jerome Powell acknowledged that monetary policy was often run for the average labour market participant, and that weaker segments of the labour market were often hurt by monetary policy which was too strongly tied to its 2% target. As a result, the Fed intended to let inflation run above 2% for some time to let these weaker segments catch up.

Another kind of 'whatever it takes'

These secondary goals of trying to correct for unfortunate side effects of policy have now been put on ice, with central banks gripped by the fear of persistent runaway inflation. The question on everyone’s mind is: can central banks reaffirm these calming anchors now, bring inflation back towards target, and at what cost?

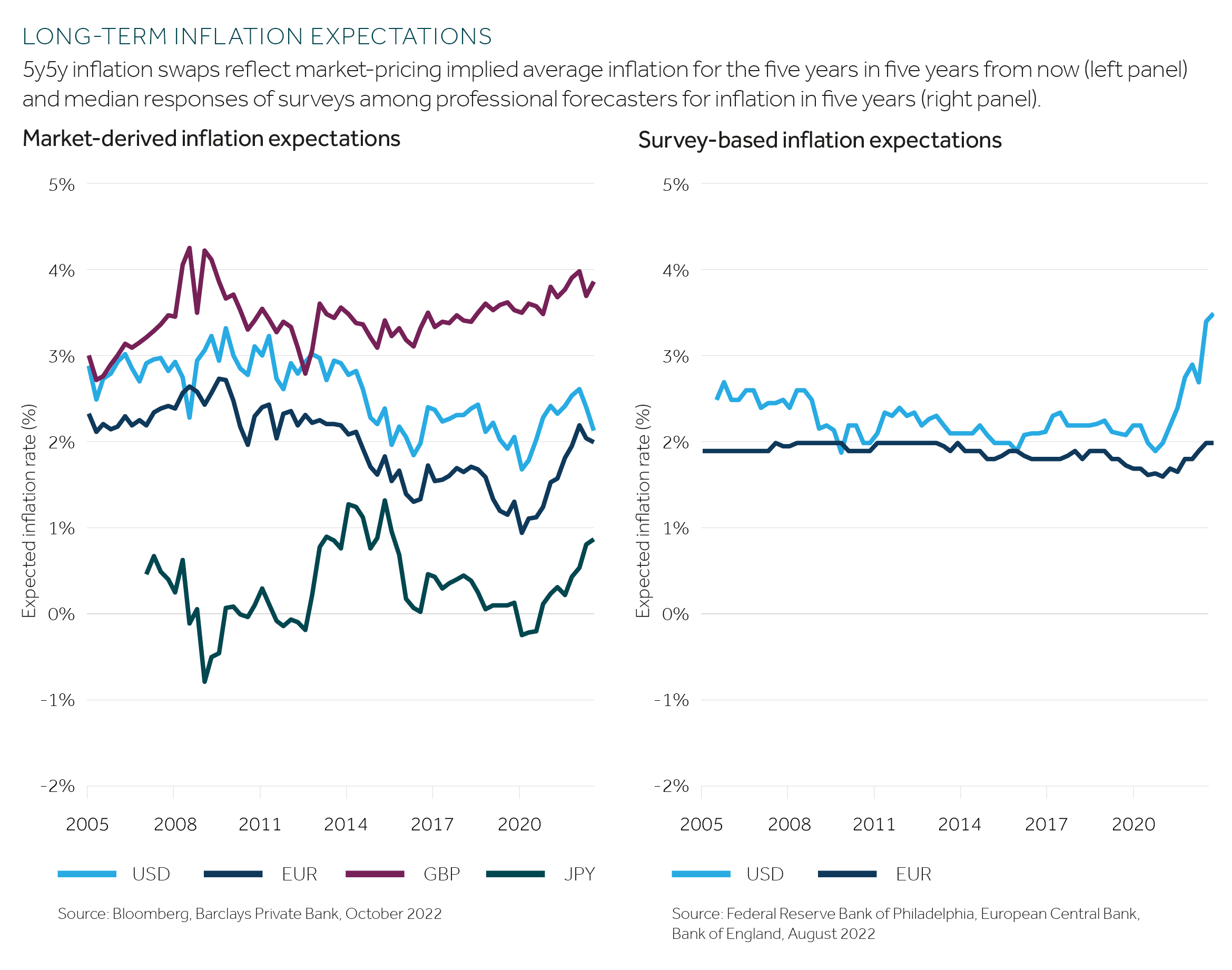

The Japanese experience of the last two decades, of having a target at 2%, while core inflation was negative almost 60% of the time since 2000, raises doubts over the ability of central banks to lift inflation expectations against entrenched structural drivers and beliefs.

Whether central banks can lower expectations is an ongoing experiment. If history is any guide, then former Fed chair Paul Volcker emphasised the need to fully commit to combating inflation, however difficult and painful it may be, in 1981, when he stated: “In sum, we are in the midst of dealing with the accumulated problems of decades. It is inevitably a painful process – precisely because it has been put off so long.”

Recent market-derived measures for long-term inflation suggest that this year’s aggressive central bank rate hikes have, for the time being, convinced market participants that inflation will return towards existing inflation targets eventually (see chart, left panel). However, the less forward-looking or less sentiment-driven measures derived from surveys and models suggest that the anchors could have risen for coming years.