The psychological need for liquidity

Some investors have reservations about private assets due to capital being locked away for a long period, typically 10 years. This can seem risky because liquidity cannot be drawn on if required.

Our desire for liquidity comes from a basic psychological need for safety. Having access to cash gives us a sense of comfort that if things don’t go according to plan, we still have a safety net. This becomes particularly important in the face of heightened uncertainty and volatility. Cash also gives an investor control over how wealth is deployed (or not deployed), which can be important psychologically.

But you may have capacity

While many investors diversify portfolios across different asset classes that they are comfortable with, the reality is that this want for comfort can underweight exposure to assets given an investor’s:

- risk tolerance - the risk in a portfolio that an investor can tolerate, based on their attitude to risk

- risk capacity - the degree of portfolio loss that an investor can comfortably manage

Many require less liquidity than they think. Due to reservations about the lock-up period for private assets, investors can end up being underweight illiquid investments. This reduces the diversification and return benefits from including private assets in a portfolio.

Misconceptions

The primary perception of investing in private assets is that money is locked up for ten or more years. In reality, the returns for investors will typically follow a “J-Curve”, where capital is committed up to approximately year six, from which point distributions will be received.

The early years of a traditional primary fund exhibit low or negative returns because the capital is employed to make investments and pay expenses. Then, as the fund’s investments mature, they generate cash flows that can offset costs, including fees and expenses. As the “harvest” phase is entered, increased cash flows from investments offset reducing capital requirements and costs, exhibiting a J-Curve.

Fund allocations

In a typical private assets programme, where frequent investment opportunities are available, those that invest into each one will find that the portfolio becomes self-funding and has a constant net asset value. The distributions received from earlier funds go into later ones.

Continuous allocation to fund commitments can maximise working capital, with target exposure being consistently achieved. A multi-vintage allocation can help weather macro events, as well as a higher degree of cash flow visibility due to the self-funding nature of the portfolio.

Additionally, the diversification benefits will be greater in the early stages of the fund’s lifecycle where there will be low beta. The correlation with public markets generally increases the closer you get to an initial public offering, and so the correlation benefits fall. As such, illiquidity also aids diversification, and investors receive higher returns as well as greater diversification.

You are compensated for holding assets

Investors also receive additional compensation for holding illiquid assets – the ‘liquidity premium’. This enhanced return that is expected for investing in illiquid assets has historically been approximately 2% on average. Over longer periods of time, the compounding effect of this premium on top of annual returns can substantially boost the wealth preservation and accumulation process.

Why do investors receive this compensation? Liquidity risk is an umbrella term that straddles two distinct, but mutually reinforcing, types of risk. The funding liquidity risk is associated with the costs of generating cash in order to meet capital commitment calls. The market liquidity risk is related to transactional costs; in other words, the ability to liquidate assets relatively quickly at minimum cost.

Funding illiquidity can pose problems for investors, especially in times of market stress. Fund managers have full discretion regarding the timing and size of capital calls. And the ability of PE investors to sell their holdings in a secondary market is severely limited due to market illiquidity.

Market liquidity risk is a consequence of various market frictions, most notably asymmetric information and complexity. In the absence of a centralised marketplace, quality data is not readily available.

Significant resources and expertise are needed to collect, process, and analyse the information. Search and discovery of investment opportunities, as well as private deal negotiations, are time consuming and costly. Therefore, many investors opt to get access to PE via funds, effectively delegating the analysis and management of companies to skilled fund managers. Highly complex PE investments incentivise fund managers to engage in relentless alpha hunting.

The end result is that investors – being liquidity suppliers – are compensated with a liquidity premium.

Some illiquidity can help

Having some illiquidity in a portfolio can be beneficial from a behavioural perspective. It helps an investor to maintain a longer-term outlook and prevent some unhelpful short-term behaviours – in particular during periods of market turbulence – in pursuit of long-term goals to protect and grow wealth.

Investors usually receive updates on the value of their private asset holdings less often than when investing in public markets, and thus may experience less portfolio volatility and smoother returns. Assets may be valued on a quarterly basis, and so during tough markets, for example, updates might be received once the period has passed, and the fund is already recovering.

An investor benefits from being shielded to some extent from short-term movements, and to some extent is locked in and prevented from panic selling. We have spoken in the past about having specific plans in place to help investors to get through difficult times; allocating to private assets can be seen as a true commitment mechanism to investing in the markets for the long term.

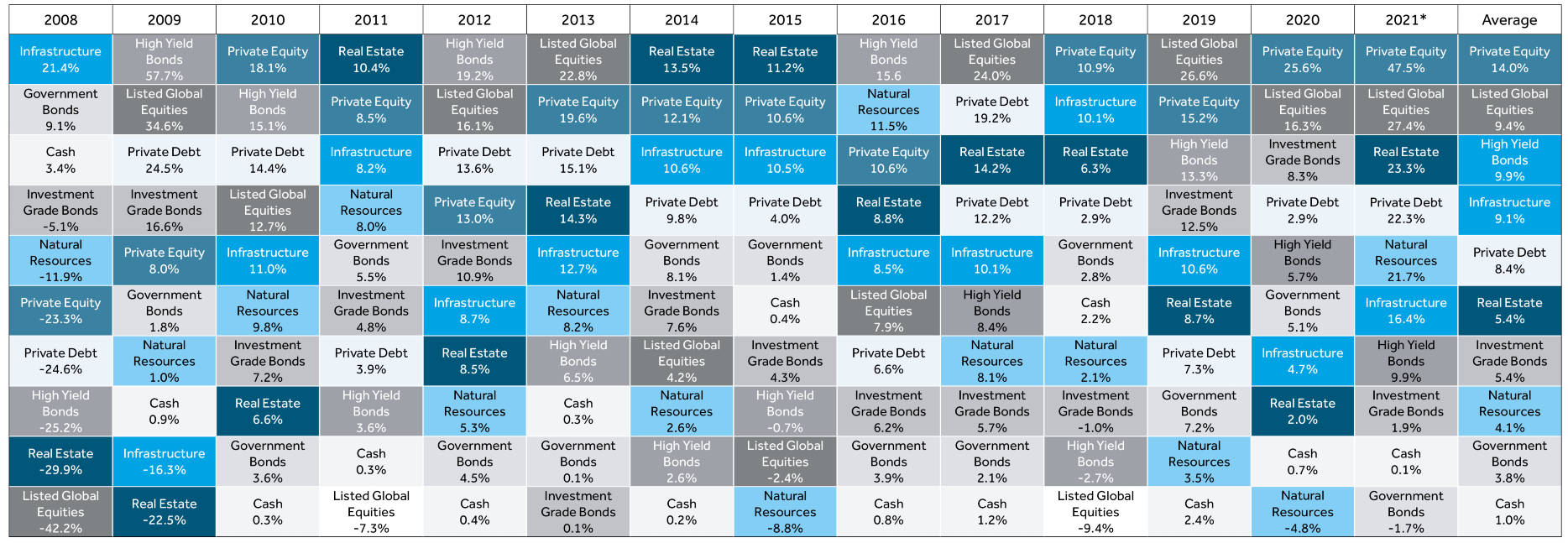

Over the long term, private assets have been shown to provide higher returns, experience lower volatility, and offer more exposure to companies than public markets do. Investors with long-term aspirations and liabilities, who are able to hold illiquid assets in portfolios, and can make significant capital commitments are best positioned to harvest the liquidity premium. From a behavioural perspective, the illiquidity associated with the asset class can help investors to stay the course in the face of much uncertainty and volatility, supporting one’s long-term goals.