Stock buybacks – the US market’s sugar rush

Over the past few years, stock buybacks in ‘Corporate America’ have surged to pre-crisis highs.

This surge has been accompanied by plenty of commentary from the press and pundits, with the majority of it being unduly critical.

In particular, many have linked the surge in buybacks to the US stock market’s remarkable post-crisis run, which recently became the longest bull-run in history.

The logic behind these criticisms is usually as follows: a stock, at its simplest level, is simply a fractional ownership of a firm’s equity.

If a firm buys back some of its shares, the proportion of the company’s earnings owned by the remaining shares increase. Without a corresponding change to the valuation of these shares, the share price would mechanically adjust upwards.

The artificial boost to the stock market

By buying back record levels of shares, US firms are artificially fuelling the stock market rally.

This line of reasoning significantly overstates the impact that buybacks have on the aggregate stock market.

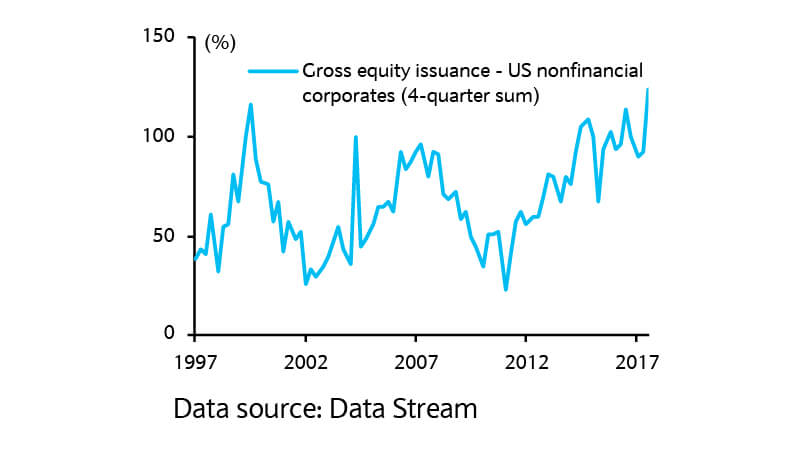

For one, the astounding buyback figures often quoted by the media focus on nominal gross buybacks. If stock markets are on average, growing in line with the economy each year, then it shouldn't be surprising that the absolute nominal level of buybacks should increase as well (figure 1).

Gross buybacks should increase with market capitalisation

Besides that, gross buyback figures exclude additional stock issuance from companies. If a company buys back one share, but issues another one immediately after, the resulting number of shares for that company remains the same.

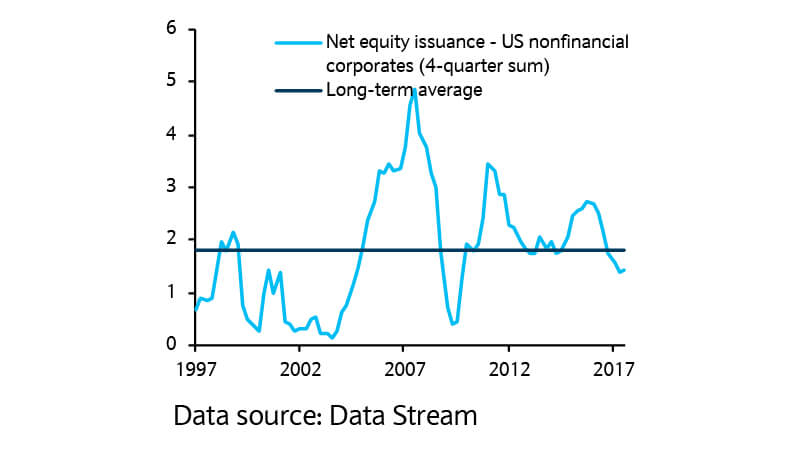

Accounting for both the increasing size of the stock market and additional equity issuance, annual net buybacks for the nonfinancial corporate sector have only averaged about 2% of the total stock market capitalisation over past years, in line with the historical average (figure 2).

Net buybacks are still in line with historical norms

As such, buybacks wouldn't have been a significantly greater driver of stock prices compared to the past.

Furthermore, such logic ignores the fact that buybacks may actually decrease earnings per share. This can be either due to forgone interest earned on the cash to fund buybacks, the loss of returns from alternative uses of cash, or higher debt servicing costs from the extra debt issued to fund the buyback.

Only if the return on cash or the cost of servicing that extra debt is lower than the firm’s earnings yield, would buybacks actually lead to the mechanical increase in earnings-per-share.

Another problem with this logic lies with the premise that share repurchases wouldn’t have a negative on the valuation. Within corporate finance theory, any increase in leverage from buybacks, either through a reduced cash stockpile or increased debt issuance, increases risk as well, which should result in an offsetting decrease in stock valuations.

As usual, the reality is much more complicated.

Share prices have, on average, been observed to increase upon the announcement of a stock buyback. There are several potential reasons for this:

- Firstly, buybacks may signal to investors that management views their company shares to be undervalued.

- Second, because interest payments are tax deductible, debt financed buybacks can be viewed as good news due to the resulting lower tax burden.

- Third, investors may feel that it is better for management to return excess cash to shareholders, rather than investing the cash in unprofitable projects.

Even if share prices do react positively to buybacks, their effects are minuscule relative to the overall performance of the equity market.

Exaggerated claims

Academic evidence suggests that the positive price impact from the announcement of a stock buyback is between 1-2% on average. If every constituent within the US stock market were to initiate buybacks at historically normal sizes within a given year, this would only lead to an additional 1-2% price appreciation at the index level, based on the academic evidence.

Viewed in context of the S&P 500’s annualised performance of about 18% per annum since March 2009, the effect of stock buybacks on the US stock market is minuscule1.

All too often, the public discourse over buybacks in ‘Corporate America’ is replete with oversimplified theories at best, or worst, glaring errors. Claims that the US stock market’s post-crisis rally is largely fuelled by buybacks are clearly exaggerated.