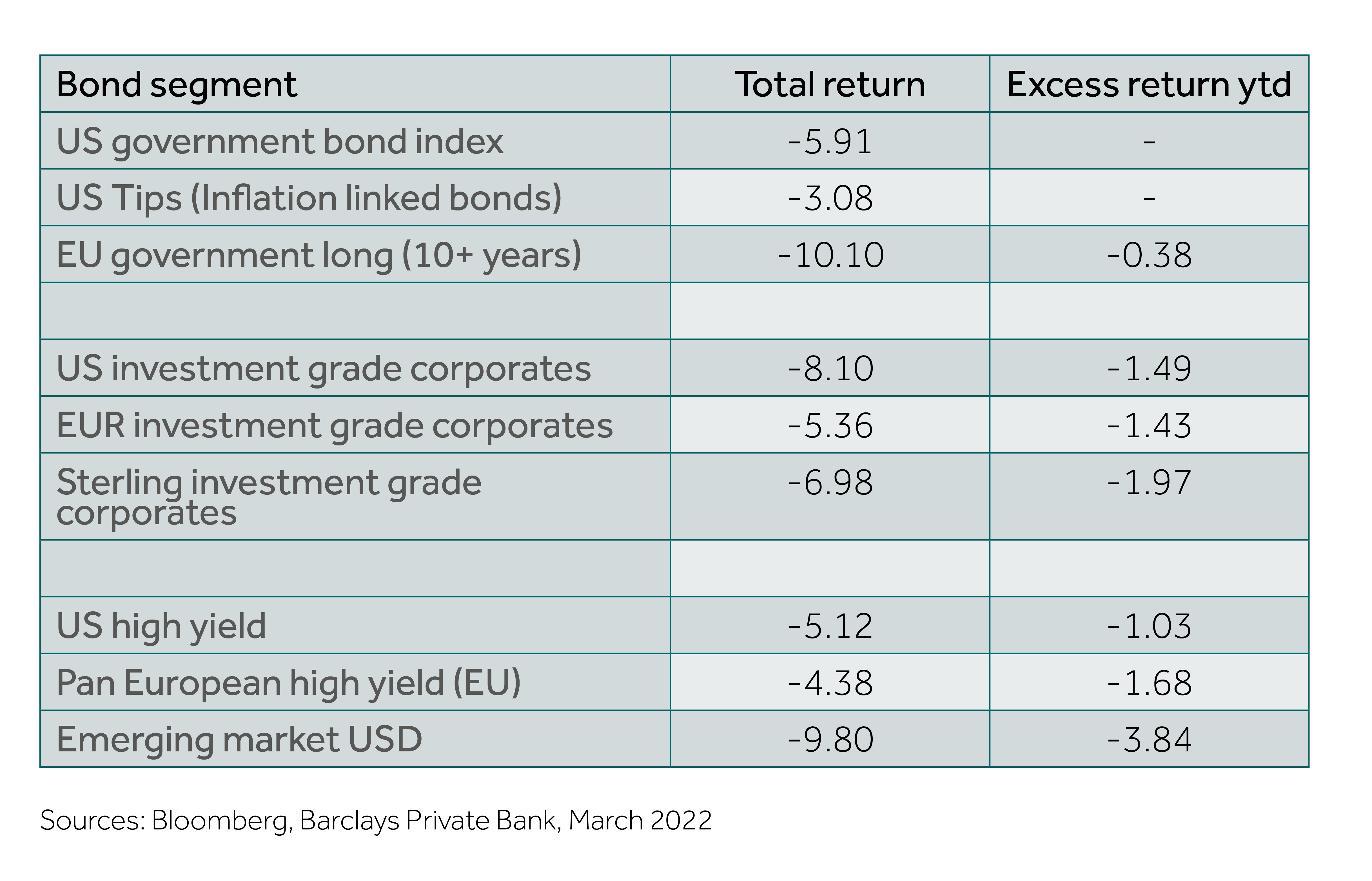

An upward moving US rate curve, driven by the front end, meant that US government bonds have lost 6.4% this year, as measured by the Bloomberg Government bond index. Wider spreads added to the pressure and led to negative excess return within corporate credit and emerging market bonds.

Central bank policy in focus

We believe that that the challenging environment is likely to persist but a selective and more defensive approach, in terms of duration and credit risk, is likely to lead to stable returns while creating pockets of opportunity.

Coming out of the pandemic, the rate market continues to be driven by central banks’ focus on tackling persistently elevated inflation. The US Federal Reserve’s (Fed) “dot plot” projection in March reiterated the central bank’s determination to fight higher prices. The median forecast places the Fed fund rate at 1.9% by the end of 2022, and points to rates as high as 2.8% in 2023, before moderating in 2024.

Revival of the flat curve

The rate market is pricing in eight hikes this year, and implies a peak for the effective Fed funds rate of over 3% by July 2023. But this level doesn’t seem sustainable, with the market implying rate cuts from there. This is a familiar story. In 2019, the rate curve started to invert, indicating that the Fed may have to revise its course, possibly due to a worsening growth outlook.

What followed was a substantial widening in spreads. This time the inversion is already visible in the forward curve, as well as the difference between the 10-year rate and the 5-year rate. Meanwhile, the 2-year rate only sits 20 basis points (bp) below the 10-year rate, and the 30-year and 5-year points, potentially hinting at challenging times for the credit market.

Curve and spreads

We reported in our Outlook 2022 that spreads can remain relatively stable during phases of curve flattening. However, when the flattening trend approaches its climax, the performance of corporate bonds tends to be subdued, and is often negative.

While the timing of spread widening varies, the flattest point during a cycle, using the difference between the 10-year and 2-year yield, was often followed by either a continuation or start of spread widening in the corporate bond segment. This could be observed in the subsequent quarters after the flattening inflection points, back in 1989, 2000, 2006, and 2019 (see chart).

Although each cycle had different triggers and features: it was at flattening inflection points that central bank rates levelled at, in hindsight, a neutral rate that was too high, while the long end started to “sniff out” growth uncertainties.

It is almost ironic that both the rate and the credit markets are very much influenced by the same pension fund buyers, which, at such inflection points, increasingly start to lock in long-end yields while they can. In addition, they often stick to spread risk until the very last moment.

A somewhat distorted view

It is hard to lean against this recurring pattern in the market which is why we prefer a more defensive approach. Still, some features of this rate cycle look different. First, as highlighted in March’s Market Perspectives, the short-end of the curve has started to price in aggressive rate hikes at an early stage, and seems to be assured by the Fed’s latest rate-path in the dot plot projections.

Usually the rate curve reaches its flattest point when the actual hiking cycle is already at an advanced stage. This time, the Fed started the cycle in March, so it could last well over 15 months from here. In addition, suppressed long-end yields appears to be adding to the flatness of the curve.

Some upward pressure for the long end

Suppressed long-end yields are probably down for two reasons. One is the substantial demand for long-duration paper by foreign buyers, be it from Japan, Europe, or other lower-yielding areas, and the large-scale bond buying by the Fed. While we do not expect a large sell-off when the Fed stops reinvesting all maturities from its Treasury portfolio, inevitably the market will demand a slightly higher yield premium, all else equal.

The second reason for lower long-end yields is the market-implied expectation for a relatively low long-term neutral rate. This is the rate that theoretically supports economic growth while keeping inflation stable, below the Fed’s target. While we also see a neutral rate of over 3% as rather unlikely, there seems a higher possibility that the neutral rate discussion is far from over, potentially leading to more volatility at the long end.

1970s world unlikely

Our base case is for higher inflation in the short to medium term, but then for it to moderate as base effects and easing of supply constraints kick in. As such, we do not expect a repeat of the long-lasting stagflation seen in the 1970s. A period that was characterised by a deep curve inversion, high default rate, and tighter financial conditions.

There are thought some parallels between the oil embargo of the 1970s and the current Russian sanctions, which requires close monitoring.

The impact of the conflict between Ukraine and Russia

According to a latest report by rating agency Moody’s, the war in Ukraine is likely to show through three channels: higher commodity prices, sanctions, and security risk, all having implications for growth.

Security risk is likely to persist in various forms, with different outcomes for the bond market. More frequent cyberattacks, pressure on domestic financials following the afflux of Ukrainian refugees, and the increased possibility of longer lasting geopolitical uncertainty, are only some factors to mention.

The conflict also carries stagflationary risks. Indeed, it adds to the challenges facing central banks as they walk on a tight rope between inflationary pressures and downside risk to the growth outlook. While leading central banks remain hawkish, it is not a surprise that the responses from the European Central Bank (ECB), the Fed, and the Bank of England (BoE) differed quite notably. While the Fed seems eager to fight inflation, the ECB, and the (previously more hawkish) BoE, seem to be treading more carefully.

European high yield most exposed

European bond issuers are clearly more exposed to the risk of higher inflation and worsening growth from the crisis than other regions. First, they face much higher energy input prices, threatening margins for many industrial companies. Second, many cyclical companies may feel second-round impacts, due to the detrimental growth and inflationary pressure facing consumers.

European high yield bonds have already underperformed materially, while US high yield bonds seem less exposed, given the country’s smaller dependencies on Ukrainian and Russian commodities. In addition, the energy part of the US market benefits from higher oil prices. This is reflected in the sector’s spreads, which are more stable, than the broader US high yield segment, this time around.

Fundamentals should be supportive

The credit fundamentals look more resilient, as the market experiences a broad recovery despite a dampened growth outlook due to events in Ukraine. Leverage is elevated, but has improved lately as earnings growth has picked up.

In US investment grade, leverage has declined to 2.4 times debt/earnings before interest rates, depreciation, and amortisation (Ebitda) from over three times. In addition, more established issuers were able to term out their funding when yields were depressed, meaning that they may have more capacity to absorb higher yields. The interest coverage (earning in relation to debt costs) has also improved and, at 12 times is at its highest level since 2014, compared to less than 10 times at the peak of the pandemic.

A similar picture is evident in the high yield market. Leverage has declined to the lowest levels in almost 10 years, and default rates, according to Moody’s, stand at 2%. Global speculative rates are prone to surge, but are likely to stay well below their long-term average of 4.1%. Admittedly, there is a risk that persisting and increasing Western sanctions on Russia push default rates higher, but it seems unlikely to push the bond market into a full blown credit crisis.

Average may not be enough

Spreads are trading below long-term average levels, and even though the fundamentals may underpin them, they are unlikely to persist, given the elevated level of uncertainty.

Outside of the pandemic, US high yield spreads hit 530bp in 2018, and 830bp in 2015 during the high yield energy crisis. While it is hard to predict the ultimate spread highs, it is clear that during indiscriminate selling episodes, opportunities will arise in more defensive sectors, such as healthcare, and sectors that can take advantage of higher energy and commodity prices.

Opportunities remain

In addition, we believe that contagion risk for the banking sector is limited. A flat curve may not be optimal, but higher rates should ultimately help the sector. Furthermore, coupons, even for subordinated debt, should be relatively stable and provide attractive yield.

Our preferred positioning remains to focus on medium-term duration bonds in the investment grade segment of the market. More defensive high yield names, including selective energy issuers and subordinated financial bonds, also appeal. More broadly speaking, even after the latest retracement in spreads, further widening is possible, if not likely. Although this means more volatility ahead, this will eventually create opportunities to lock in higher yields in the future.