In Switzerland

We wanted to celebrate our 35 years in Switzerland by publishing a collection of interesting stories from some of our clients and partners with whom we work.

28 June 2021

8 minute read

Thierry Mauvernay is interviewed by Elsa Floret

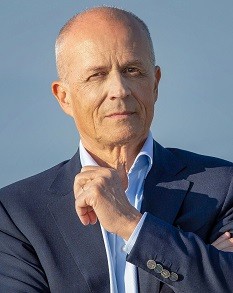

Thierry Mauvernay

President, Debiopharm

Thierry Mauvernay is the president of Debiopharm, a Swiss laboratory that specialises in the development of pharmaceuticals.

After studying medicine and pharmacy at the University of Strasbourg, Thierry’s father, Rolland-Yves Mauvernay, who was born in 1922, set up his first pharmaceutical research laboratory in the Auvergne in the early 1950s.

Within 20 years, the acquisition of various competitors had resulted in it becoming a large regional laboratory that had discovered several new chemicals. In 1973, he decided to sell his French undertakings and start from scratch once again by launching a new laboratory in Switzerland dedicated to the development of therapeutic drugs.

Vision for the future

The Debiopharm adventure began in 1979, and during its more than 40-year history the company has developed several drugs, including triptorelin, which is used to treat certain prostate cancers. Following Rolland-Yves’s death in 2017, Thierry took over the company he had joined in 2001 and directed since 2011.

Thierry Mauvernay had initially announced to his father that he would never work with him. This wasn’t because he didn’t love and respect him – on the contrary, he had always adored his father. Rather, it was because his father had a strong personality and Thierry wished to avoid any tension arising between the two.

So, in 1976, at just 23 years of age, Thierry launched his own cosmetics company in Paris. Over time, the company expanded into nearly 40 countries. After managing it for over 20 years Thierry sold the company in 1998, although he remained in charge until 2001. It was around this time that he reversed his earlier decision and joined his father at Debiopharm in Switzerland. In the beginning his remit focused mainly on administration and strategy, but ten years later he became co-president and managing director.

You like to quote André Malraux, who predicted that the 21st century would either be spiritual or not. Do you agree, and what characteristics do you believe values and spirituality have in common?

The quest for spirituality forces us to leave the material world and reflect upon our own values. These are important. They serve as a compass for our actions and prevent us from becoming self-centred. Without values, we would probably live only for ourselves.

Values enable us to go beyond ourselves and consider others and the environment. Values enable people to identify with each other and unite. It is likely that, without patriotic values, hardly anyone would be prepared to go to war to defend their country, for example.

A year after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, how do you think the world and society are likely to change in the future?

We will probably return to much of the pre-COVID-19 world, but there will be an increasing number of quick societal changes, and many patterns will certainly be broken as well. People will want to live as they did in the past, and that is normal. We will need and want to re-establish the social ties that were broken or put on hold during the pandemic.

At the same time, certain changes that we have seen will become more pronounced and will persist; these include working from home, e-commerce and how people view climate change. There will also be disruptions that will put an end to certain business models. We will view things such as leisure time, health and mobility differently.

Some professions will be paid greater respect. We will probably find ourselves in a relatively unstable situation for some time. Unlike in the post-war era, infrastructure has not been damaged: the old world is still there, but a new one is beginning to emerge. We will have to find our bearings.

As the pandemic runs its course, governments will probably realise that they will have to do more to prevent and defend themselves against future pandemics. For example, they will need to build up healthcare supplies, just like they do for food, oil and weapons. Over the next ten years, Switzerland, for example, is much less likely to experience a war than a new pandemic.

I hope that governments realise that they also need to provide anti-bacterial and anti-viral security. In the future, armies alone will be unable to protect a country and enforce its sovereignty. We have always seen the enemy as a state or people, but we now realise that a bacterium or a virus can be an even more threatening enemy – much more dangerous than any army. In the fight against such opponents, borders no longer exist.

You have rebranded your asset management company to Après-demain (the day after tomorrow). What values do you think will be most important in the future?

This term is a tribute to my father. For him, the timeline of pharmaceutical research wasn’t about tomorrow but rather the day after tomorrow – in other words, the future. Debiopharm invests for the long term. I like to recall that after man reached the moon in 1969, the French philosopher Michel Serres commented that humanity had reached the wrong conclusion.

The moon landing should not have been famous for marking the beginning of the conquest of space, as has often been emphasised, but for the realisation that the Earth is a small planet and that the vast majority of humanity will have to continue living on it for thousands of years. We are destined to live together in a small world.

We are, and will be, confined to this planet for a long time and we must take great care of it, just as we must be attentive to, and inclusive of, our neighbours. For me, it is clear that all of our means must be focused in this direction.

What does success mean to you?

I deplore the apology of success. There is a tendency, unfortunately, to think that success is natural. But it is failure that is natural. If I don’t take care of my garden, it will become a wasteland. We praise the successful, but we must be aware that they are only a small minority. Pharma is the archetype of this state of affairs and people should not be afraid of failing in this field, as it is a business that involves failure. Just one molecule in 10,000 becomes a drug.

This is not a reason to despair and give up – on the contrary, you have to have strong convictions and stay the course in the face of the many failures you will inevitably face. Debiopharm’s strength is in its resilience by selecting only one molecule out of 600 per year, which has been built up over the years building on our experience.

I once had the opportunity to meet Usain Bolt, the fastest sprinter in history, in Lausanne. When I asked what was special about him, what made him win so many races, he said: “I learned how to lose before learning how to win.” He was in his twenties. I was impressed. Lots of people will never win, so those who are privileged to do so should, as far as possible, help other people.

Focus on the next generation

Your son Cédric, who is 36 years old, is expected to take over the company. What is his philanthropic focus?

My son Cédric is a member of the board of Next, our family foundation, and also the board of the Debiopharm Chair for Family Philanthropy at the International Institute for Management Development (IMD). He is personally very interested in issues surrounding the preservation and protection of the environment. As a young father who has just taken over the management of La Solution.ch SA, he unfortunately lacks in time. Philanthropy enables the family to unite around our common values.

However, there are times in life when we are more aware of these themes and sometimes when we are more available than others. Therefore, it is important to remain inclusive, knowing that the various family members may be more or less able to get involved depending on the stage they are at in their lives and the time they have available.

What future projects does your family’s Next foundation have in its sights?

Our purely philanthropic activity is based on four pillars: education, helping the poor (including through micro- and nano-credit), integrating immigrants into society, and autism.

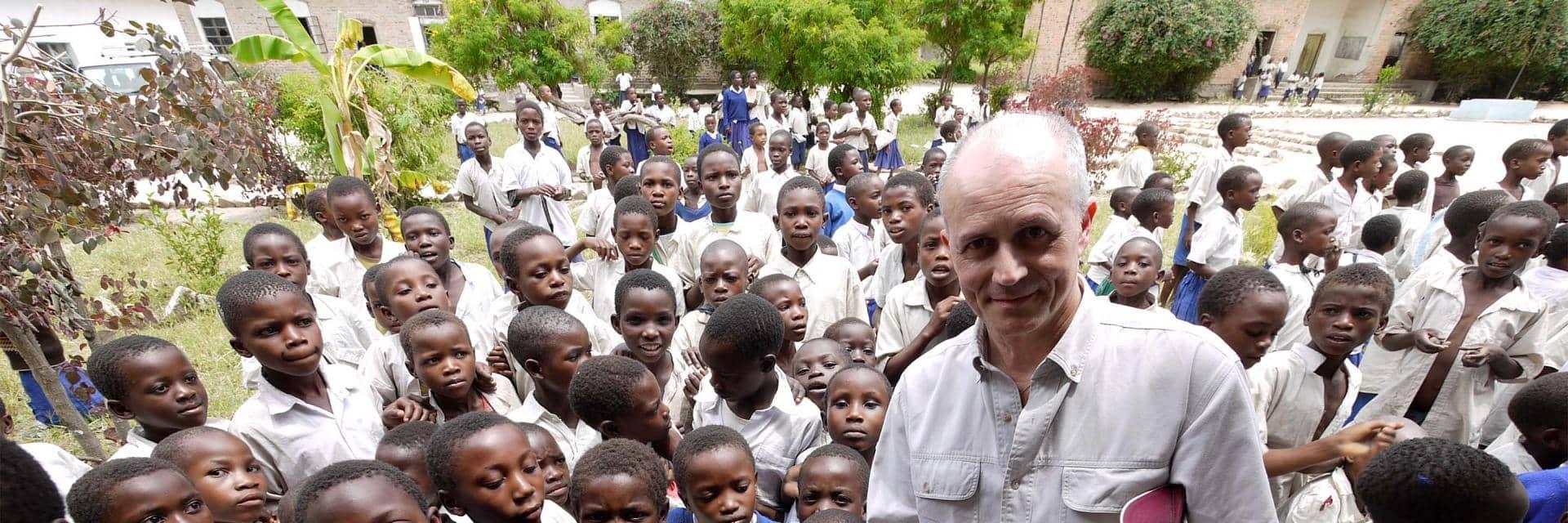

The Next philanthropic foundation works towards the first of these four objectives by supporting the education of street children in several countries: Vietnam, Cambodia, South Africa, Tanzania, Indonesia and Lebanon. Secondly, it is involved in helping immigrants integrate into Swiss society.

It is important not just to welcome people from other countries into Switzerland, but also to give them the chance to integrate well, especially professionally, because work is a powerful means of integration. We finance two integration programmes in Geneva and Lausanne. Third, the foundation aims to combat extreme poverty in emerging countries.

By creating overseas educational programmes and micro-credit programmes to finance micro-businesses, we hope to have a positive impact on more than 50,000 people per year. We also seek to reduce extreme poverty in Switzerland through the Mère Sofia Foundation, which provides meals for the disadvantaged, for example. The fourth pillar of Next’s philanthropic activities is supporting people with autism, taking action in five fields: housing, leisure, education, health and work. Our projects with autism are under the direct responsibility of my wife.

Debiopharm employs 450 people from 43 different nationalities. What is the secret to uniting people?

People are united by common projects and values. Today in Switzerland, most people can choose their career path and who they work for. Of course, we have to be realistic – they work for a salary and a quality of life, but giving meaning to their work is important to them, as is finding meaning in the company’s values. Another unifying element is success: we must be able to share our success. Employees must be able to be proud of the company they work for, and philanthropy contributes to such feelings of pride.

Are you afraid of a generation gap with the next generation?

I am indeed. The current crisis has created a wedge between generations. Young people realise this and ask: how much does supporting the elderly cost us? This may have become more apparent when four people of different generations were forced to turn a small kitchen into a temporary office during the pandemic so that they could work from home. It will not be easy to bridge this growing generation gap.

Today, a generation no longer covers a 20-year period, but rather five to seven years. There is a huge gap that is widening. In our company, we strive to enable six different generations – each with different needs and objectives – to grow together. It’s a challenge. Any unifying element is therefore important.

The Debiopharm Chair for Family Philanthropy at IMD, Lausanne

Family companies – which account for more than 70% of the world’s businesses – are major contributors to the global economy, society and philanthropy. You created the Debiopharm Chair for Family Philanthropy at IMD in Lausanne with the aim of increasing the social and financial impact of donor families. Four years after its creation, has this Chair reached its target?

The Chair was created in 2016, but it was not fully up and running until 18 months later when Professor Peter Vogel, who is a Professor of Family Business and Entrepreneurship, was recruited as the Debiopharm Chair for Family Philanthropy as we wanted to wait for someone with the necessary credentials to take up the position. New programmes are being implemented at the IMD. A philanthropy course is now on offer and a book has been published on family philanthropy. Our Chair has a 15-year horizon, giving us the time we need to build something sustainable.

By endowing the Debiopharm Chair for Family Philanthropy at IMD, you supported the publication of a book entitled Family Philanthropy Navigator: The Inspirational Guide for Philanthropic Families on Their Giving Journey, which was co-written by Peter Vogel, Etienne Eichenberger (WISE) and Malgorzata Kurak (IMD).

Absolutely. This book makes an important contribution to how the needs and role of philanthropy are evolving, in line with the mission of the Philanthropy Chair at IMD. Ultimately, I hope this book can be a catalyst to improve the state of the world through family philanthropy. It should be soon translated into several languages, including Chinese.

In the foreword, you focused on three pillars: philanthropy and social impact, managing donations effectively, and the fact that donating also benefits the donor. Let’s consider each of those pillars in more depth. Philanthropy and social impact: spontaneous giving often does not achieve the expected results or reach the right people. Are you saying that giving shouldn’t be carried out without careful thought?

Philanthropy is wonderful, but resources are always limited, and it can be extremely harmful if they are not used optimally. Unlike other philanthropy chairs, which generally train people to work in that field, we have chosen to train philanthropists themselves. Through leverage, a donation of CHF100 can have an impact almost comparable to that of CHF1000 or even CHF2000.

Very often, philanthropy is carried out impulsively. Of course, one’s emotions should be involved, but to have a real impact, philanthropists must not be governed solely by emotion. They must act with a long-term vision and with the aim of building or participating in a programme. Good intentions are not enough to make a good philanthropist.

A good philanthropist is someone who selects projects, analyses them, helps to carry them out, and checks that they are being carried out effectively and that the money has gone into the right pockets. Because in my opinion, we are partly responsible for how the money being given is actually used. For example, after the Haiti earthquake in 2010, 95% of the donations did not end up going to the people they were intended for.

Managing donations effectively: philanthropy requires rigorous and professional management, even if the desire to help others often stems from emotions. How would you define a professional approach to philanthropy?

If the donors were as professional in giving as they are in their professional life, we could help a lot more. Professional philanthropy is built around projects. The Bill Gates Foundation, for example, has set the goal of eradicating malaria. You can unite your family and employees around long-term, sustainable projects whose progress can be measured.

For example, we have encouraged our employees to use elevators less and the stairs more because it is better for their health, and we donated the savings in energy costs to the Telethon. We have also replaced water fountains and bottled mineral water with water that we carbonate ourselves. We donate the resulting savings to Helvetas, which helps people without access to drinking water. The money we have donated has been used to purify approximately 5 million litres of water.

Donating also benefits the donor: very often, money divides people rather than brings them together. How great is the risk of alienating the different generations?

Money can divide us: it is one of the biggest sources of discord within families. That’s a shame. And it’s not easy to overcome the divisions it creates. Philanthropy has the advantage of uniting everyone around common values that go beyond the short-term interests of the individual by supporting projects that everyone can agree on. In my opinion philanthropy is a powerful means of bringing family members together.

We wanted to celebrate our 35 years in Switzerland by publishing a collection of interesting stories from some of our clients and partners with whom we work.