Smart cities: spotting the post-pandemic opportunities

12 February 2021

5 minute read

Julien Lafargue, CFA, London UK, Head of Equity Strategy

The COVID-19 pandemic is changing how we live, learn, work, consume and invest. Cities are feeling the brunt of the effects. Those that the grasp the significance of the changes and the opportunities they offer may be able to adapt better than most.

You can also download this report as a PDF - Smart cities report [PDF, 572KB]

Some argue that this crisis has simply accelerated secular trends while others think it has introduced profound changes to our lifestyles. What seems clear is that the world after the COVID-19 pandemic will be different. As the centre of modern life, cities are at the heart of this post-pandemic transformation. To respond to this challenge, cities need to become smarter, potentially creating significant opportunities for investors.

Cities matter

The top 600 cities are projected to account for 60% of global GDP by 2025

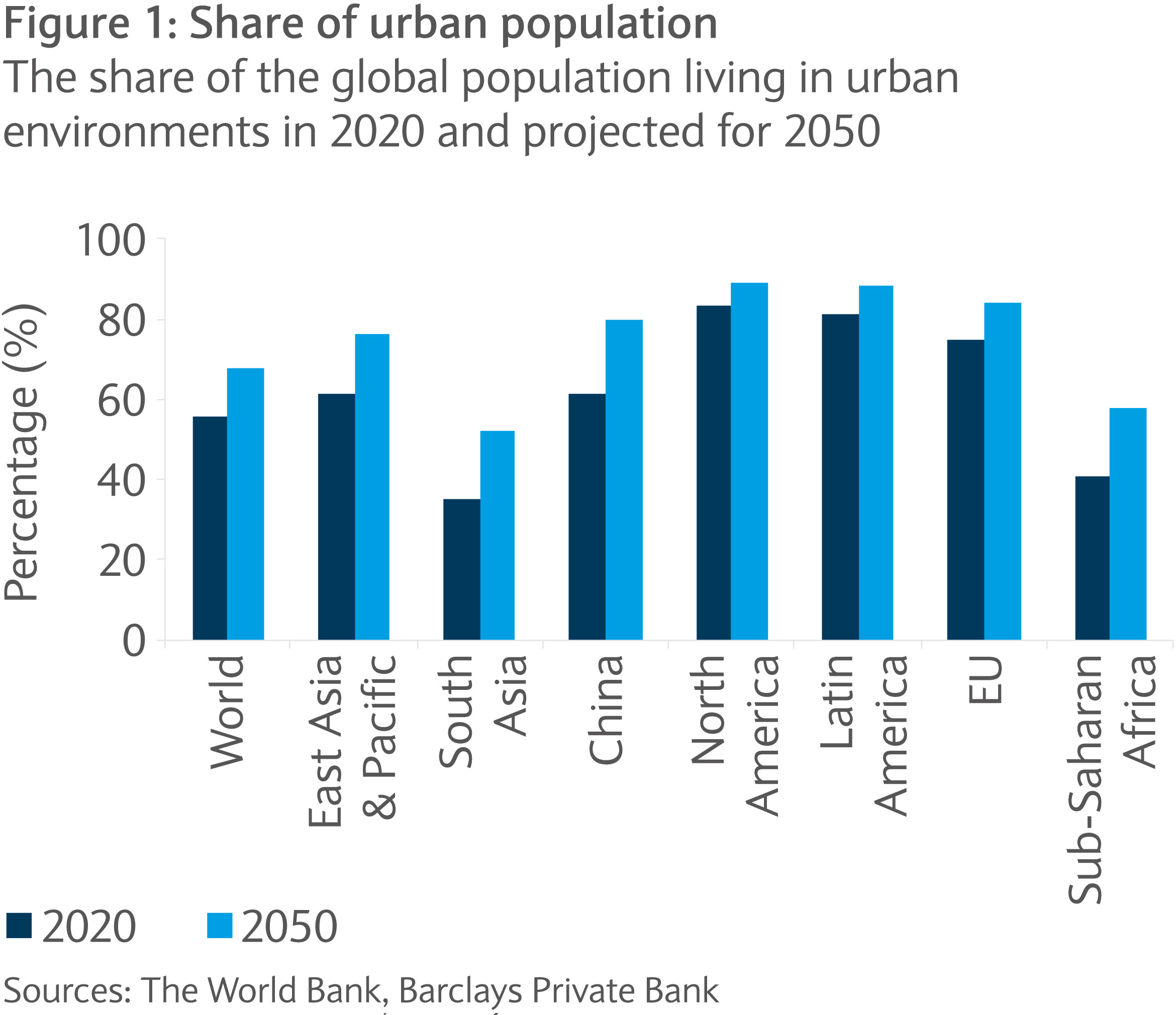

Urbanisation has been around for centuries. Some historians argue that the first cities emerged in ancient Mesopotamia some 4,000 years ago. Since then, there has been a constant and accelerating exodus away from rural areas. By the 1600s, about 3% of the world’s population was living in cities of 20,000 or more. By the middle of this century, this number is likely to balloon and be closer to 70%.

As a result, urban environments have become the centre of economic growth. According to the World Bank, they are now contributing 80% of global gross domestic product (GDP) and the top 600 cities are projected to account for 60% of global GDP by 2025, found consultancy firm McKinsey1 (see figure 1).

Urban challenges

The expansion of cities hasn’t come without challenges. Some of those are well documented: housing supply/demand imbalance and affordability issues, inadequate infrastructure development (creating time losses from traffic congestion), increasing social divides and rising criminality rates.

More recently, with climate change becoming a major threat, the focus has moved to environmental considerations. Indeed, although cities occupy only 3% of the Earth’s land mass, they consume around two-thirds of the world’s energy and drive around 75% of global carbon emissions, according to the United Nations2. As a result, at least 90% of the urban population worldwide is breathing air with a level of particulate matter over the value recommended by the World Health Organization guidelines3.

The COVID-19 effect

With most large cities being locked down and a majority of companies allowing their employees to work remotely, the COVID-19 pandemic has shed a new ray of light on city living. First, with economic activity more limited, air quality in major metropolises improved significantly, with a knock on effect on people’s health.

Second, with less need to commute to work, people have considered relocating further away from city centres, perhaps in the hope of more relaxed lifestyles. This is also true for broader consumption trends with retail centres and high street shops losing market share. As a result, the future of real estate within cities, whether its housing, commercial or offices, is likely to suffer.

Finally, the pandemic has laid bare some potential disadvantages of living in densely populated areas, including:

- Faster spread of infections, especially in low-quality, overcrowded housing

- Increased stress posed to ill-equipped public services in time of crisis

- Difficulty in tracking and tracing people with COVID-19 infections, even when relying on technology such as smartphone apps.

Smarten up

“Smarter” cities may be a useful way of addressing the above challenges. Smart cities aim at using recent disruptive technologies to help meet demographic, economic, environmental, infrastructure and social challenges. Essential elements of a smart city include next-generation infrastructure, smart services, an enabling environment and empowered citizens.

The concept of smart cities isn’t new. In 2015, as part of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the United Nations highlighted “sustainable cities and communities” as a pillar to transforming our world. While not explicitly listing smart cities, the UN’s guidelines clearly support the advent of new ways to plan, run and live in urban environments.

Now is the time

The issues brought to the fore by the COVID-19 outbreak show the urgency to act. While cities have regularly changed to meet shifting demands, perhaps becoming more efficient, inclusive and safer, they now have the need and the fresh tools to make changes. Indeed, the development of next-generation technologies (known as nextgen) such as 5G, broadband, big data and cloud computing, are opening up many potential solutions to cities’ most urgent problems.

In addition, the demand for such changes, in the shadow of the pandemic, has never been stronger. Whether it’s coming from citizens who have realised the dangers associated with air pollution or from local governments looking for ways to run their cities more efficiently to make up for lost revenues caused by COVID-19, interests appear aligned for smart cities to become reality.

The state of play

Like autonomous driving for cars, a city can exhibit degrees of “intelligence” in attempts to make life easier. In its most basic form, a city can be “connected”, such as allowing citizens to conduct administrative tasks online.

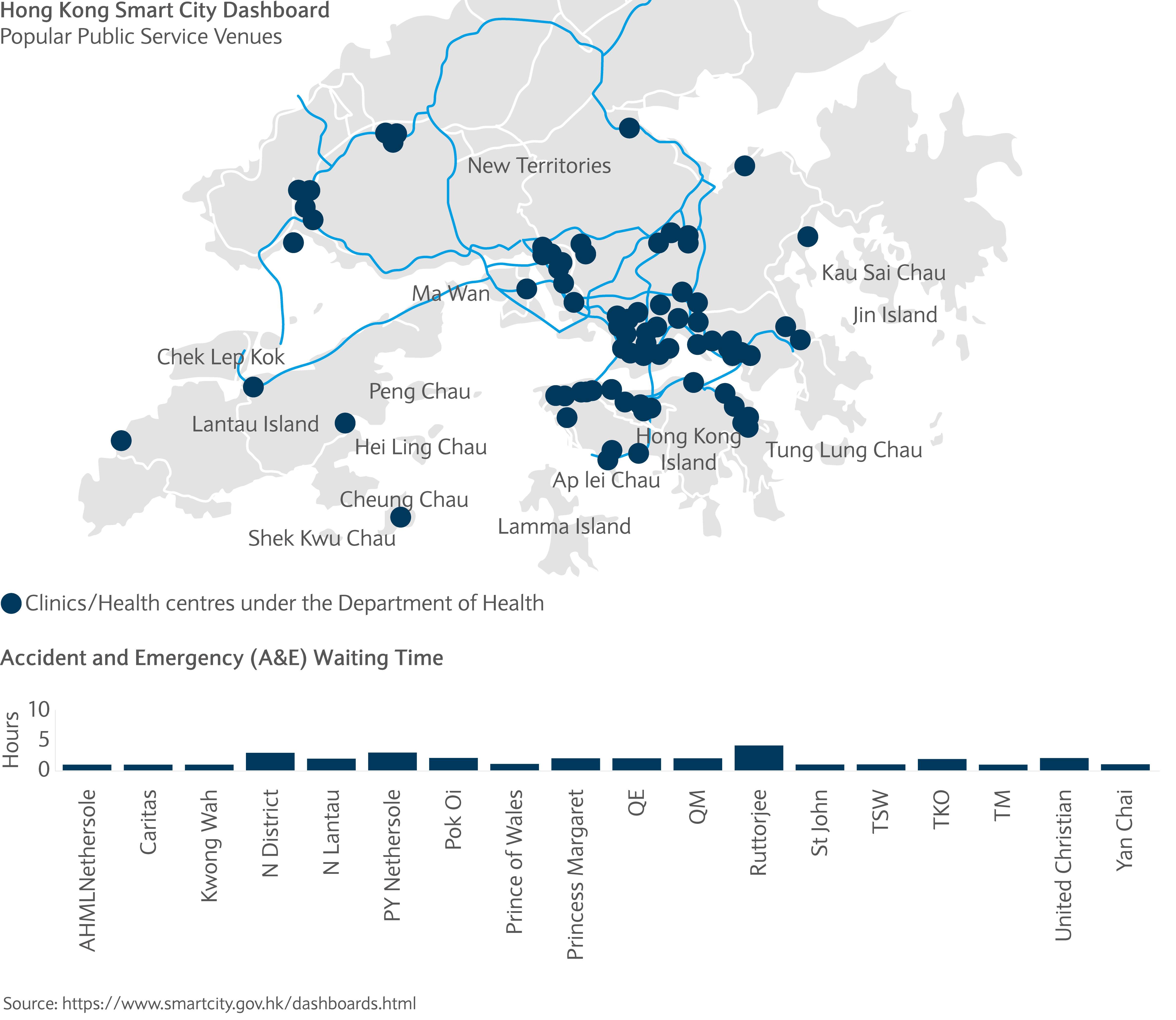

As connectivity improves, a city can become more “integrated”, merging operations and allowing multi- city-agency efforts (perhaps like Hong Kong’s smart city dashboard, below). Pushing the boundaries further, cities may start offering “personalised” services such as location- specific deliveries or ad-hoc traffic-congestion alerts. Finally, a smart city can adopt “predictive” capabilities relatively easily.

At this point, most capitals in the developed world are “integrated” cities but “personalised” and “predictive” abilities are still in their infancy.

The next step

Technology is the main enabler in the pursuit of smarter cities and with that, connectivity is critical. Indeed, to precisely monitor and provide to the community, local authorities must be able to pinpoint needs and demand, in real time. Until now, select connectivity was possible but there were significant hurdles to make it ubiquitous. With 5G networks, this is about to change.

The fifth generation of mobile networks combines high-speed connectivity, very low latency and universal coverage. These attributes will allow the “Internet of Things” (IoT) to become mainstream. This allows digital information to be sent from anything from a rubbish bin or lamp post to an ambulance or airport in real time. The applications of this technology are endless, with wide-spread implications. As the hub of most people’s life and the beating heart of economic activity, cities have a lot to gain.

Sizing the opportunity

Grand View Research puts the global smart cities market size at around $464bn by 2027

With a broad smart cities theme, quantifying the opportunity is a challenge in itself. Grand View Research puts the global smart cities market size at around $464bn by 2027, registering a near 25% compound annual growth rate from 20204. Others prefer to focus on the global infrastructure needs required to meet expected economic and population growth. McKinsey puts this number at $3.7tn per year to 2035 with an additional trillion dollars required to meet the UN sustainable development goals and transition towards smart cities5.

Irrespective of the method used to quantify it, what’s clear is that, as cities get smarter many sectors will be impacted and, like with any other paradigm shift of that magnitude, there will be many winners and losers.

The future of real estate

The pandemic has acted as an accelerant for cities’ transformation. In particular, lockdowns and the need to work from home or social distance are forcing a rethink of real estate usage.

Offices have been hit particularly hard. According to a report by property specialist Savills, the vacancy rate in Manhattan jumped to 15.1% in 2020 from 11.1% in 2019, the highest rate in data going back to 1999. That left 68.4m square feet (6.4m square metres) empty6. While a vaccine may bring back workers to their desk, people’s expectations of where to work from are shifting. As many as 72% of workers now want a hybrid model of sharing work between home and the office, according to Future Forum Research7.

With more people likely to work from home, housing is also changing with prospective buyers’ main criteria moving away from an easy commute towards increased space both indoor and outdoor. Similarly, communication is replacing transport as the network of choice.

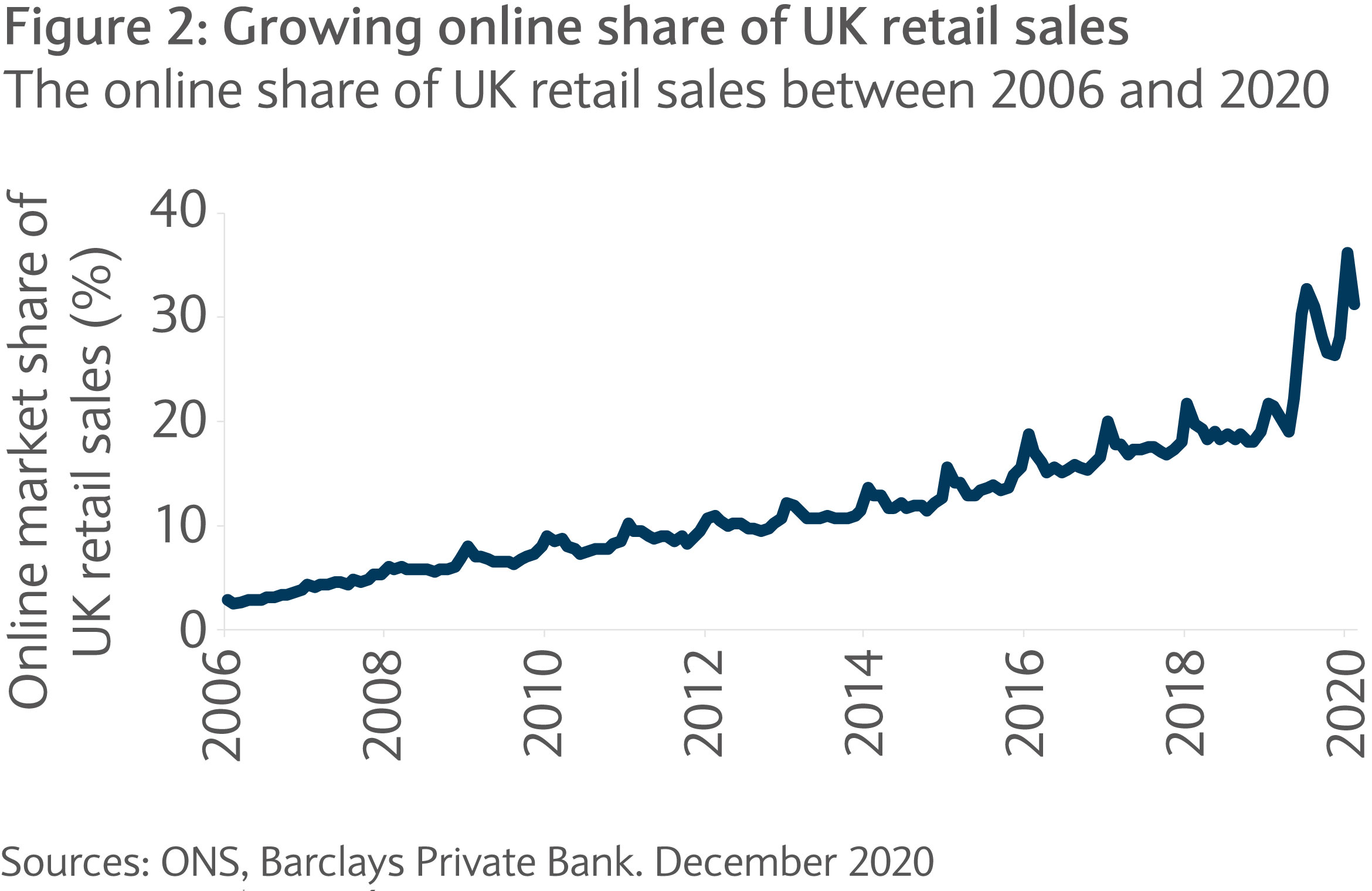

Finally, with people deserting city centres, retail is changing too with online commerce penetration increasing rapidly and sales boosted by the pandemic. In the first two weeks of December 2020, Salesforce estimates that global digital sales rose by 45% year on year to a staggering $181bn.

While a “return to normal” could see bricks-and-mortar shops recovering some market share, their outlook remains bleak. As more sales take place online (see figure 2), retail space in city centres is likely to shrink and be repurposed. For shops, keeping a physical presence and adopting marketing that links the online and store experience should increase dramatically.

Tackling climate change

As cities compete to remain attractive, they are likely to be a key driving force in the promotion of sustainable development, well ahead of states

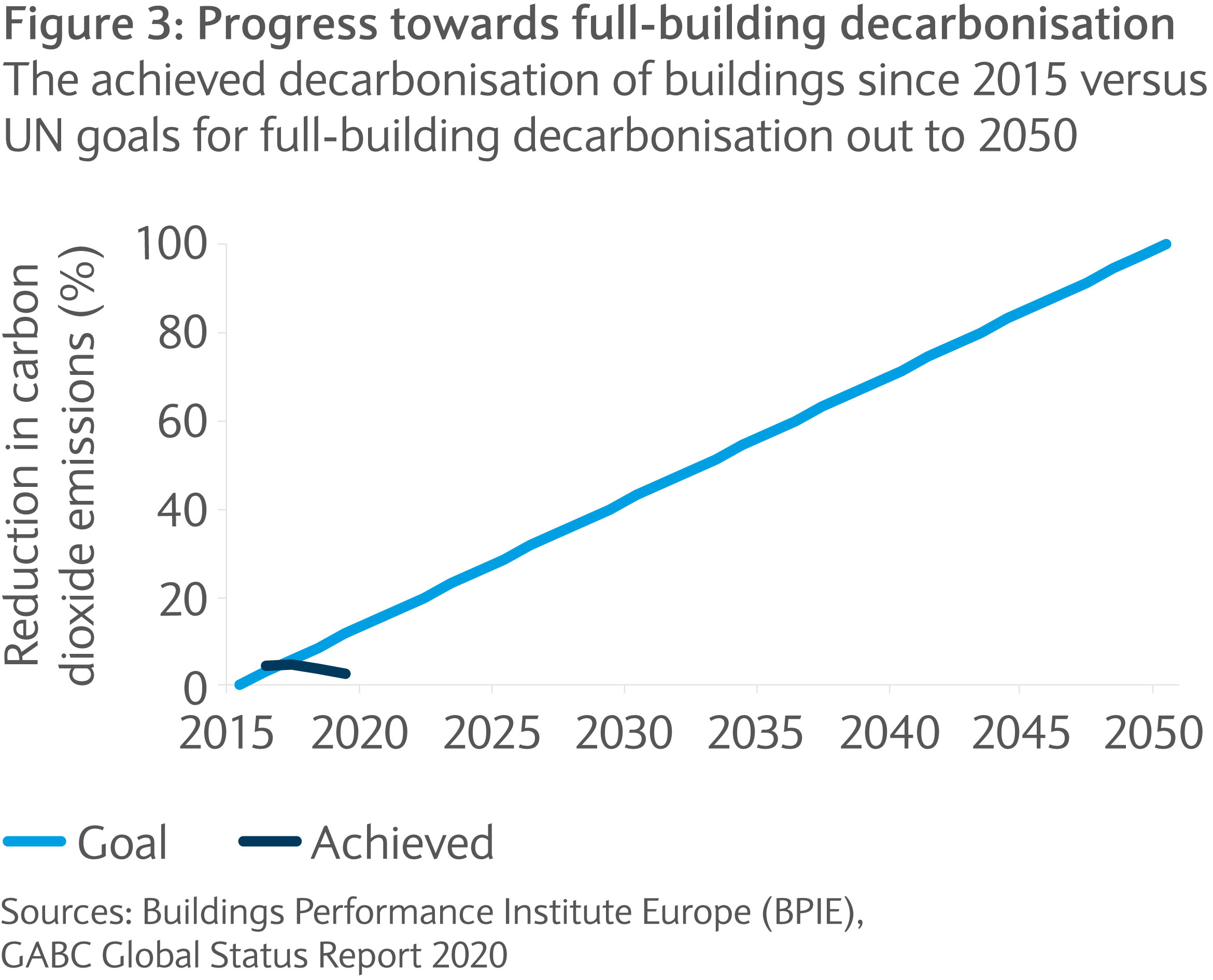

Although it’s currently eclipsed by the COVID-19 healthcare crisis, climate change probably remains the biggest challenge facing us. Here again, cities are central to the problem and the solution. As mentioned previously, cities account for 70% of CO2 emissions (buildings contributing more than half of that). If nothing is done, there is a danger that some conurbations become unlivable.

The energy used in London office buildings is equivalent to the amount used to power over 65,000 homes and is costing London businesses up to £35m per year, according to think-tank Green Alliance8. Therefore, there are strong incentives, both financial and environmental, for cities to become net zero carbon by 2050 as advocated by the World Green Building Council and implied by the Paris Agreement. There is much to do. For instance, while carbon dioxide emissions from buildings are being cut, eliminating such emissions by 2050 is a long way off (see figure 3).

As cities compete to remain attractive, they are likely to be a key driving force in the promotion of sustainable development, well ahead of states or regions. This includes new building regulations, fiscal incentives and forcing multi-sector collaboration to encourage better use of resources. This is only achievable with the right infrastructure in place, reinforcing the case for smarter cities.

Investment implications

There should be a wide array of opportunities for investors looking to gain exposure to the theme of “smart cities”. We divide the opportunities into three sub-themes to help with targeting potential investment ideas:

Smart buildings: The way buildings whether there are industrial, commercial or residential, are built and operated will likely be the most prevalent change seen as cities become smarter. Smart buildings will be more efficient, more connected and sustainably integrated to their environment.

Infrastructure (communications and transport): In order to become smarter, cities will also need to rely on improved infrastructure. This is both at the physical level with more intelligent roads, transport links and public services and at the digital level with nextgen networks (such as 5G and fibre) and connectivity (the IoT and cloud).

Energy and waste management: A smart infrastructure should allow for more efficient management of resources both upstream (generation of energy and grid transmission) and downstream (waste collection and recycling), bringing to life the concept of economy.

| Smart buildings | Infrastructure | Energy and waste management |

|---|---|---|

| Building and automation | 5G and telecommunications | Energy production |

| Energy efficiency | Software and hardware | Grid management |

| Sustainable construction | Internet of Things | Waste and recycling |

Source: Barclays Private Bank

Related articles

Investments can fall as well as rise in value. Your capital or the income generated from your investment may be at risk.

This communication:

- Has been prepared by Barclays Private Bank and is provided for information purposes only

- Is not research nor a product of the Barclays Research department. Any views expressed in this communication may differ from those of the Barclays Research department

- All opinions and estimates are given as of the date of this communication and are subject to change. Barclays Private Bank is not obliged to inform recipients of this communication of any change to such opinions or estimates

- Is general in nature and does not take into account any specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of any particular person

- Does not constitute an offer, an invitation or a recommendation to enter into any product or service and does not constitute investment advice, solicitation to buy or sell securities and/or a personal recommendation. Any entry into any product or service requires Barclays’ subsequent formal agreement which will be subject to internal approvals and execution of binding documents

- Is confidential and is for the benefit of the recipient. No part of it may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted without the prior written permission of Barclays Private Bank

- Has not been reviewed or approved by any regulatory authority.

Any past or simulated past performance including back-testing, modelling or scenario analysis, or future projections contained in this communication is no indication as to future performance. No representation is made as to the accuracy of the assumptions made in this communication, or completeness of, any modelling, scenario analysis or back-testing. The value of any investment may also fluctuate as a result of market changes.

Barclays is a full service bank. In the normal course of offering products and services, Barclays may act in several capacities and simultaneously, giving rise to potential conflicts of interest which may impact the performance of the products.

Where information in this communication has been obtained from third party sources, we believe those sources to be reliable but we do not guarantee the information’s accuracy and you should note that it may be incomplete or condensed.

Neither Barclays nor any of its directors, officers, employees, representatives or agents, accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct, indirect or consequential losses (in contract, tort or otherwise) arising from the use of this communication or its contents or reliance on the information contained herein, except to the extent this would be prohibited by law or regulation. Law or regulation in certain countries may restrict the manner of distribution of this communication and the availability of the products and services, and persons who come into possession of this publication are required to inform themselves of and observe such restrictions.

You have sole responsibility for the management of your tax and legal affairs including making any applicable filings and payments and complying with any applicable laws and regulations. We have not and will not provide you with tax or legal advice and recommend that you obtain independent tax and legal advice tailored to your individual circumstances.

THIS COMMUNICATION IS PROVIDED FOR INFORMATION PURPOSES ONLY AND IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE. IT IS INDICATIVE ONLY AND IS NOT BINDING.

Important information

-

Urban world: Mapping the economic power of cities, McKinsey, March 2011Return to reference

-

Sustainable Cities: why they matter, the United NationsReturn to reference

-

9 out of 10 people worldwide breathe polluted air, but more countries are taking action, World Health Organisation, May 2018Return to reference

-

Smart Cities Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Application (Governance, Environmental Solutions, Utilities, Transportation, Healthcare), By Region, And Segment Forecasts, 2020 – 2027, Green Alliance, February 2020Return to reference

-

Unlocking private-sector financing in emerging markets infrastructure, McKinsey, October 2019Return to reference

-

Manhattan Office Vacancies Soar to a Record With Leasing Frozen, Bloomberg, January 2021Return to reference

-

Coronavirus: How the world of work may change forever, BBC, October 2020Return to reference

-

Energy wasted by the City of London’s offices could power over 65,000 homes, Green Alliance, January 2020Return to reference