Outlook 2021

Barclays Private Bank investment experts highlight our key investment themes and strategies for the coming twelve months.

19 November 2020

9 minute read

By Alexander Joshi, London UK, Behavioural Finance Specialist

This year may have been unusually unpredictable and tough for investors. But every year is full of unexpected events. Well-diversified, actively managed portfolios may be the best protection for 2021.

We expected the biggest risk to financial markets would come from an unexpected event in last year’s Outlook 2020. Indeed, the world faced a big unexpected event. A global health crisis in the form of the COVID-19 pandemic induced the fastest ever bear market sell-off and shut down economic activity across the globe. The repercussions will probably be felt for years.

Uncertainty has been elevated this year. How the pandemic evolves remains unknown, with major uncertainty still surrounding almost every aspect from a health, societal, economic and political perspective. Importantly, this applies to developing and deploying a safe, effective vaccine that will be key to the lifting of restrictions and the economic recovery.

The impacts of this health crisis – an external shock to markets – were initially expected to be transitory. However, they may alter behaviours. A prime example is remote working and its implications for many sectors of the economy. Consumers across the world have reported new shopping habits since the start of the pandemic (63% in the UK, 73% in the US, 86% in China and 96% in India). Globally they are expected to continue these behaviours for some time1.

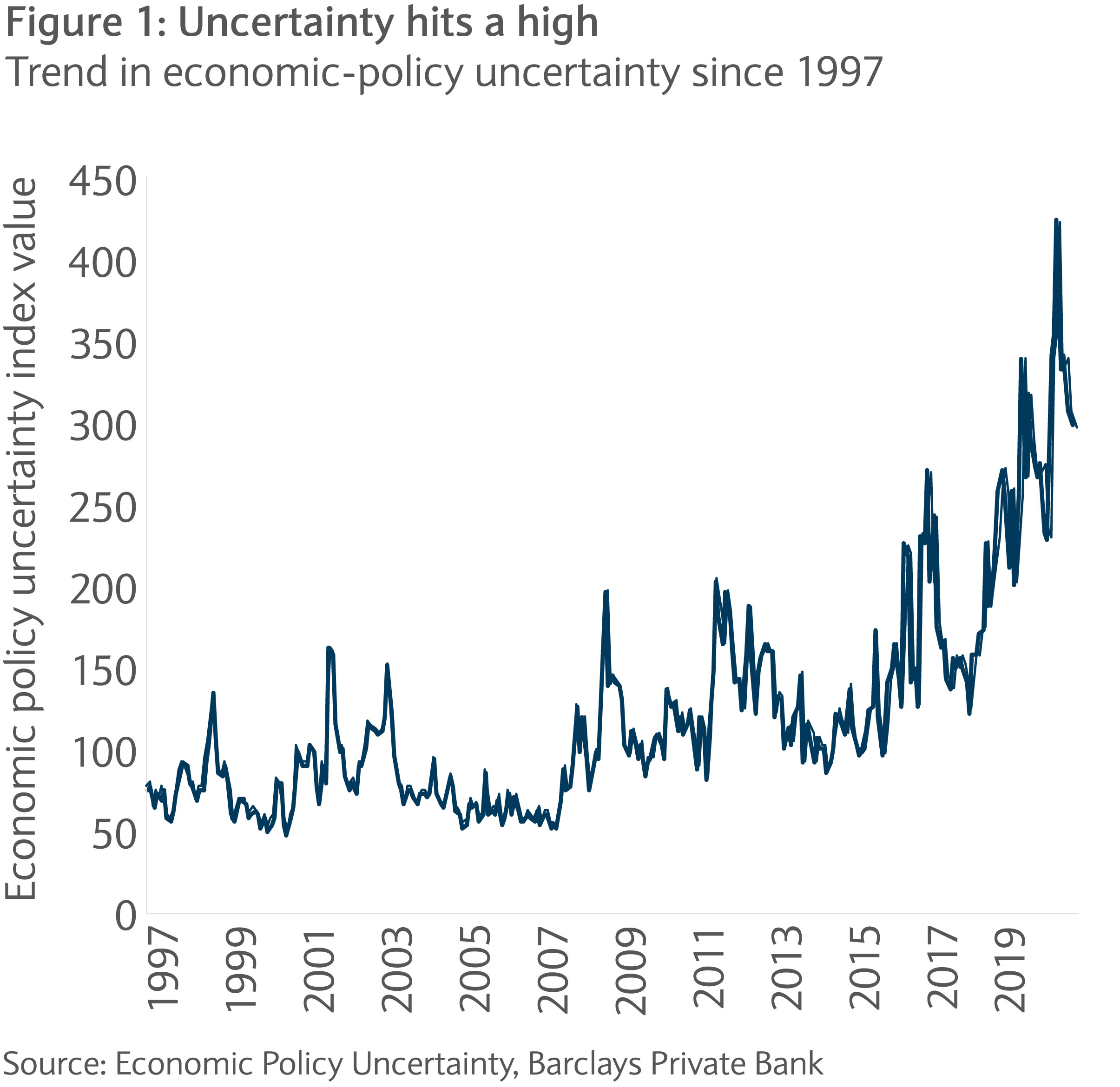

While 2020 has been an extreme case, with global economic-policy uncertainty rising to its highest level since the index began (see figure one), every year in investing is difficult to predict. When stating that things are more uncertain what is usually implied is that something has changed that makes the future increasingly tough to forecast. But has it? The fact an event that wasn’t predicted happened doesn’t necessarily mean uncertainty has increased. Instead, unanticipated events illustrate how the uncertainty was understated prior to the event.

Elevated volatility can make staying invested in the markets challenging for investors. While most of the focus for investors this year has been on the pandemic, geopolitical uncertainty as always waits on the horizon, with the fallout from the US election and Brexit prime candidates of that. All this is against a backdrop of macro themes that will continue, as well as the possibility of any manner of external shocks. Climate change will become an ever-increasing risk too.

Therefore, it could be prudent to hold portfolios that are positioned to protect assets during such periods and help investor weather those storms.

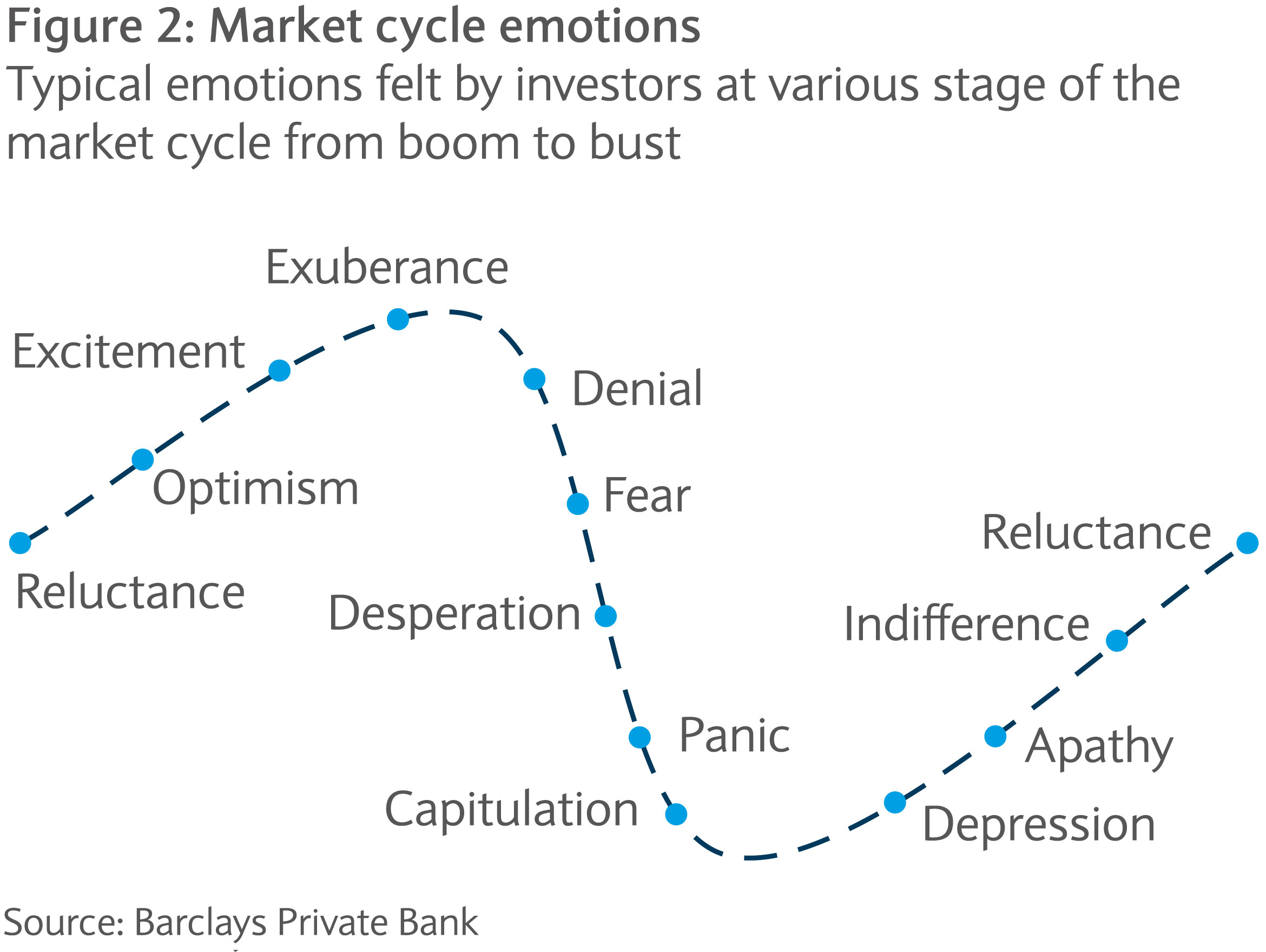

Behavioural biases can manifest themselves throughout a market cycle. They can be especially pronounced during crises, when emotional responses are heightened. Investors typically feel a predictable series of emotions during the course of the cycle (see figure two) making it easier to get invested when markets are rising, but may also induce selling during downturns. This can lead to the opposite of “buy low, sell high”.

Periods of heightened uncertainty, volatility and falling markets can trigger fear and panic and the first instinct of investors may be to sell or reduce risk. Holding falling assets, combined with uncertainty over when the bottom will be reached, can take a toll on investors. This is a natural response; when your portfolio is at risk, your long-term goals are too.

It is when markets look most precarious that our behavioural proclivities can lead us astray. These problems are compounded when volatility rises suddenly like earlier this year, with the VIX, which reflects the volatility implied by options on the S&P 500, rising over 500% in the 4 weeks to its 16 March peak. Only days after US equities reached all-time highs, large parts of the global economy were essentially turned off overnight and previously low unemployment rates shot up. At the index’s low, 23 March 2020, the S&P 500 had plunged by 33.9% from its 19 February top.

The speed with which events unfold (and short news cycles) can exacerbate stress levels and anxiety. In turn, this can shorten investment time horizons, which may make investing appear riskier. The biases that manifest themselves, such as the impact of the fear of losses and uncertainty about their size, can affect an investors’ ability to weigh risks and lead to overreactions which can damage wealth aspirations.

While this year seems an extreme example, markets move in cycles and our reactions to them are largely systematic. Being aware of the ways in which we can react to negative news that may not be in our best interests, might not be enough to prevent us repeating them. It is human nature.

Good investing discipline involves being cognisant of and planning for individual behavioural tendencies. A robust investment process which has diversification at its core can help achieve this.

The traditional case for a diversified portfolio is that by investing in many asset classes it should lower portfolio volatility due to imperfect correlations between assets. The overall variability of a portfolio’s returns becomes less than the weighted sum of its constituents. By allocating across assets, the idiosyncratic risks of each are usually diluted.

However, a common criticism of diversification is that this smoothing can fail when most needed. During market sell- offs and melt-ups, assets can move in sync as correlations spike. The market appears to behave as one.

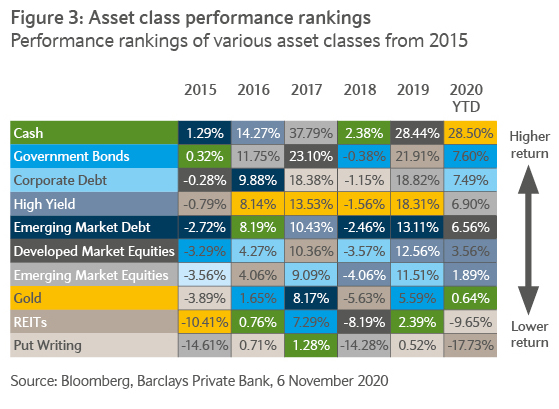

Instead, the aspect of diversification which is more important to consider relates to the performance rankings of asset classes (see figure three), which tend to change year on year and are difficult to predict. A portfolio that is concentrated in a single asset class might be invested in the worst performing one over a given period (as well as, of course, the very best). Conversely, the performance of a diversified allocation should not be at either of the extreme ends of the spectrum. This not only makes financial sense, but also has behavioural benefits.

Diversification not only insulates an investor from volatility by smoothing out returns. It may also dampen the behavioural reaction in turbulent periods and profit from time in the market. Volatile and falling markets can trigger panicked decision-making, typically involving selling assets. However, much of this might reflect emotional liquidity running low, not financial liquidity. Investors panic.

An investment strategy can’t be successful if an investor is unable to stick with it consistently. Following a robust investment process, that leads to a diversified portfolio, can help investors stay invested by limiting the emotional reaction to market volatility.

Good investment decision-making requires asking yourself whether events are likely to affect your ability to reach your long-term goals. A diversified portfolio allows an investor to turn down the noise on market commentary when short- term news flow can make suboptimal decisions more likely. A portfolio allocated across asset classes, geographies and sectors is unlikely to fully experience the impact on markets of headline market moves. Investors should also remind themselves of their investment time horizon. It is likely to be far longer than that of market commentators fighting for airtime and visibility.

Not all diversification is created equal. Part of good asset allocation rests on reliable estimates of long-term returns, interactions of asset classes and not high conviction. Good diversification is not just about increasing the number of holdings but involves the necessary sophistication to both protect a portfolio and enhance risk-adjusted returns. This is especially important in a low-return world.

The traditional 60-40 equity-bond portfolio allocation seems to be less effective in delivering the desired returns in a low-rate environment, eroding diversification attributes. Financial markets have become more dynamic and complex systems, making it preferable to build portfolios that provide carefully tailored, multi-factor exposure.

The traditional 60-40 equity-bond portfolio allocation seems to be less effective in delivering the desired returns in a low-rate environment

Diversification doesn’t just protect an investor, but it may also allow calm investing while others are heading for the exits. Diversification in itself is not an investment strategy. Long-term investing using active management seems an attractive proposition. This means not just investing in the market, but having a long-term focus and investing in high- quality companies. Those with superior and sustainable business models that are expected to outperform for years to come.

Diversification is not just about picking an allocation and leaving it. Investors can still be opportunistic as long as the right balance is found. Following a robust process which balances long-term thinking with generating the core investment returns, while allowing reactive and opportunistic tactical tilts to allocations, can maximise returns and mitigate risks.

A particularly volatile period in an uncertain, post-pandemic world may create potential market dislocations, providing potential opportunities for active managers to capitalise on.

Barclays Private Bank investment experts highlight our key investment themes and strategies for the coming twelve months.

Barclays Private Bank provides discretionary and advisory investment services, investments to help plan your wealth and for professionals, access to market.

This communication:

Any past or simulated past performance including back-testing, modelling or scenario analysis, or future projections contained in this communication is no indication as to future performance. No representation is made as to the accuracy of the assumptions made in this communication, or completeness of, any modelling, scenario analysis or back-testing. The value of any investment may also fluctuate as a result of market changes.

Barclays is a full service bank. In the normal course of offering products and services, Barclays may act in several capacities and simultaneously, giving rise to potential conflicts of interest which may impact the performance of the products.

Where information in this communication has been obtained from third party sources, we believe those sources to be reliable but we do not guarantee the information’s accuracy and you should note that it may be incomplete or condensed.

Neither Barclays nor any of its directors, officers, employees, representatives or agents, accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct, indirect or consequential losses (in contract, tort or otherwise) arising from the use of this communication or its contents or reliance on the information contained herein, except to the extent this would be prohibited by law or regulation. Law or regulation in certain countries may restrict the manner of distribution of this communication and the availability of the products and services, and persons who come into possession of this publication are required to inform themselves of and observe such restrictions.

You have sole responsibility for the management of your tax and legal affairs including making any applicable filings and payments and complying with any applicable laws and regulations. We have not and will not provide you with tax or legal advice and recommend that you obtain independent tax and legal advice tailored to your individual circumstances.

THIS COMMUNICATION IS PROVIDED FOR INFORMATION PURPOSES ONLY AND IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE. IT IS INDICATIVE ONLY AND IS NOT BINDING.

Consumer sentiment and behavior continue to reflect the uncertainty of the COVID-19 crisis, October 2020, McKinsey & CompanyReturn to reference